Introduction

Justin Trudeau stood defiant on 24 October 2024 and declared four days before the deadline that he would stay on as leader of the Liberal Party and Prime Minister in defiance of about one-fifth of Liberal MPs: “We’re going to continue to have great conversations about what is the best way to take on Pierre Poilievre in the next election, but that will happen with me as leader going into the next election.” [1] The Liberals had met in caucus and devolved into grouptherapy for three hours on the 23rd; backbenchers wanted to feel heard and attempted to orchestrate a half-hearted ousting of their leader, and therefore the Prime Minister of Canada, by asking him nicely and without threatening any repercussions. Many backbenchers broke down into long-winded and faintly absurd, emotive diatribes on political television; Ken Hardie best exemplified the psychobabble when he declared, “We have to process this” before CTV News.[2] I so sorely wish that Canadian broadcasters could hire some British journalists to grill our unsuspecting politicians; I’d especially love to see Krishnan Guru-Murphy of Channel 4 take unguarded delight in skewering some of these Liberal backbenchers with his trolling mirth or Jeremy Paxman in his prime mercilessly mock the mealy-mouthed and the meek.

Ministers must maintain collective responsibility and solidarity and therefore provided only short quips in brief scrums. Francois-Philippe Champagne celebrated not merely the “great discussion” but lauded it as “the type of discussion that Canadians would be proud to see.” Sadly for us though, discussions within caucus remain confidential. Defence Minister Bill Blair similarly praised the meeting as “healthy” and “robust.” Various journalists reported that Justin Trudeau himself also became emotional; The Hill Times says that Trudeau spoke “with tears in his eyes,” and Catherine Cullen of CBC News said that Trudeau also expressed dismay over the increasingly ubiquitous “Fuck Trudeau” flags and how they affected his children who also bear that surname.[3]

Too few of the 24 backbenchers who presented Trudeau with a letter – which omitted their names – outlining their objections have even bothered to come forward. Before the meeting, only Sean Casey of Prince Edward Island, Ken McDonald of Newfoundland and Labrador, and Wayne Long of New Brunswick had identified themselves. New reporting later named Ken Hardie and Patrick Weiler of British Columbia, Yvan Baker of Ontario, George Chahal of Alberta, Sameer Zuberi of Alberta, Ali Ehasassi of Ontario, Parm Bains of British Columbia, and probably also Alexandra Mendes of Quebec (given what she has said in public).[4] That only accounts for 11 of the 24. Anthony Housefather and Joel Lightbound of Quebec have also both become well-known for expressing their disagreements with the government in public. John McKay of Ontario also did not seem particularly happy with Trudeau’s statement and regretted that the Liberals had not adopted the Reform Act in the 44th Parliament back in 2021, because it would have given the will of the parliamentary party “clear expression.”[5] McKay even contradicted the initial statement of Liberal Caucus Chair Brenda Shanahan, who told The Hill Times in 2021 that the Liberals rejected all four provisions of the Reform Act “unanimously” and insisted that he had supported adopting them three years ago.[6] That probably brings the tally up to 14.

Several MPs resigned themselves to their own powerlessness and simply declared “That’s up to him” in response to the question on whether Justin Trudeau should resign the leadership and premiership. Even Wayne Long, one of the first backbenchers who publicly called on Trudeau to resign, concluded: “Ultimately it’s his choice. I’m just personally disappointed that it’s less than 20 hours after many of us told him he had to, or we thought he needed to step down. He told us he would reflect. It’s pretty quick reflection and I think he needs to reflect more.”[7] Sean Casey likewise declared that he found Trudeau’s announcement “disappointing.”[8] Casey also lamented to The Hill Times that the Liberal caucus decided not to adopt the Reform Act in 2021 for the duration of this 44th Parliament, because those procedures “would have made everything much clearer.”[9] Sadly, in Canada, this is true. That decision tends to fall to the leader and not to the caucus. Trudeau joins a long line of near-invincible Canadian prime ministers. How did this happen? How can British and Australian parliamentary parties brutally and swiftly oust their leaders and prime ministers while their Canadian counterparts cannot?

Delegated Leadership Conventions Turned the Prime Minister into an Ersatz President

Ultimately, Canada’s iron party discipline stems from American innovations that Canadian political parties imported in the 1910s and 1920s. In Canada, we have over the last century cultivated an ersatz presidentialism and created semi-invincible and sessile prime ministers who can only resign the party leadership after losing an election, but not because the parliamentary party or cabinet oust them from office. Until a century ago, the parliamentary party alone elected and ousted party leaders. Australian political parties still follow this tradition today. But this changed in Canada after the First World War. After the Conscription Crisis of 1917, most English-speaking Liberal MPs had abandoned Laurier and joined Sir Robert Borden’s Conservatives in a temporary wartime coalition. Sir Robert Borden restructured his ministry and invited 9 Liberals and 1 Labourite to join a new Unionist administration,[10] and these Liberals even ran with the Conservatives in the election of 1917 as a coalition, which lasted until July 1920.[11] The venerable Sir Wilfrid Laurier led the Liberal Party for an astonishing 32 years, from 1887, through his premiership from 1896 to 1911, and until his death in 1919.

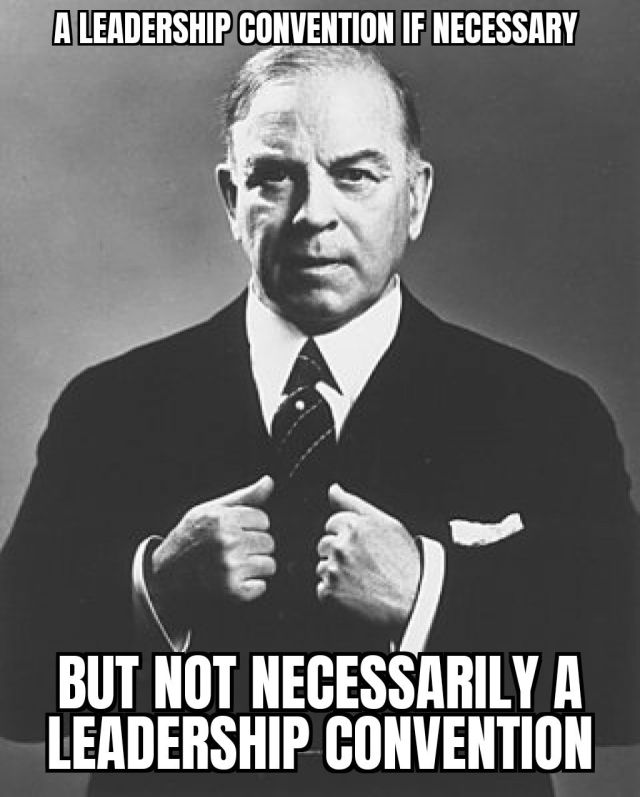

Laurier had originally scheduled a policy conference for 1919 that would chart the party’s course after the Great War; after his death, the Liberals decided to stage a delegated leadership convention instead. The Liberal parliamentary party selected David D. McKenzie expressly as an interim leader and abdicated its own authority to elect future party leaders.[12] McKenzie ran for the leadership at the convention but lost to William Lyon Mackenzie King, a former MP and Minister of Labour under Laurier who remained loyal to Laurier’s legacy.[13] Canadian historian John Lederle remarked: “It is interesting to note that the temporary leader selected by the parliamentary caucus, himself a candidate for the leadership at the convention, did not automatically got the leadership mantle.”[14] The Conservative Party adopted the same style of delegated convention to elect R.B. Bennett as leader in 1927.[15] The New Democratic Party also elected its leaders by delegated conventions from 1961 until 2003, when it gave that power to the members of the party themselves. The Reform Party and Canadian Alliance also gave each party member one vote.

Mackenzie King led the Liberals to tentative victory in 1921 in Canada’s first minority parliament since Confederation, to near-defeat in 1925 in another minority parliament in which Arthur Meighen’s Conservative won the plurality of seats, and, finally, to a majority in 1926 after the King-Byng Affair. King lost to R.B. Bennett’s Conservatives in 1930 but won another majority and began his third non-consecutive term in 1935, winning another big majority in 1940 and a large plurality in 1945 before retiring in 1948.[16] Such a lengthy tenure as party leaders, both in government and opposition, would not happen today and indeed has not happened since King. Mackenzie King also sired the myth of the ersatz presidential party leader in Canada owing to the unprecedent manner of his selection as leader of the Liberal Party.

King told his cabinets and the Liberal parliamentary party at some points between 1919 and 1948 that since a delegated convention had elected him as party leader, only a delegated convention could remove him as party leader; in King’s self-serving estimation, the delegated convention had abolished the parliamentary party’s authority to elect and oust leaders altogether.[17] King considered himself “the representative of the party as a whole, not merely of the parliamentary group” and further believed: “What the parliamentary group did not create it may not destroy, at least not without ratification by the party ‘grass roots.’ The leader may appeal beyond the caucus to the party membership.”[18] John Lederle first reported on King’s Doctrine in 1947; former Liberal cabinet minister J.W. Pickersgill corroborated Lederle’s account of The King Doctrine in an interview with political scientist John Courtney in 1969.[19] The idea that party leaders elected through delegated conventions could likewise only be ousted through delegated conventions quickly took hold and became the conventional wisdom of Canadian politics in the 20th century – despite being a totally false and factually incorrect contrivance that contradicts all parliamentary tradition and common sense.

One precedent from the late 19th century illustrates how cabinet and the parliamentary party could oust leaders, and another federal precedent from the early 21st century shows that the parliamentary party still holds great sway in practice. If a party leader cannot maintain the support of the parliamentary party, then he realistically cannot remain as leader, irrespective of whether the broader membership of the political party has expressed their opinion or not. In January 1896, the Conservative cabinet staged a revolt against Senator Prime Minister Sir Mackenzie Bowell, made Sir Charles Tupper the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons and de facto Prime Minister, and forced Bowell to resign the premiership formally in April 1896.[20] Canadian historian Barry Wilson points out that:

“Bowell became the first sitting prime minister and party leader in British parliamentary history to be forced from office by his own caucus despite the fact that he led a majority government. Another century would pass before Canadians again witnessed the spectacle of a prime minister and party leader who commanded a majority in Parliament (Jean Chretien) being pushed into resignation by dissenters fighting an in-party civil war for power.”[21]

Jean Chretien Embraced the King Doctrine

No recent former prime minister has articulated the King Doctrine as clearly and unambiguously as Jean Chretien. On 22 August 2002, after months of bitter in-fighting within the Liberal Party, Prime Minister Jean Chretien finally announced that he would resign as leader of the Liberal Party and Prime Minister in February 2004.[22] But events compelled him to resign instead in December 2003. Chretien made this announcement while the House of Commons stood adjourned for summer recess at the Liberal parliamentary party’s annual retreat and not in the House of Commons itself or outside of the prime minister’s offices at what was then called Langevin Block. Liberal MPs never openly called upon Chretien in the House of Commons itself to resign the premiership, and the Liberal parliamentary party accepted what the press dubbed Chretien’s “Long Goodbye” of over one year. If any Liberal MP had publicly denounced him, Chretien would simply have kicked them out of the parliamentary party and refused to sign off on their nomination papers as Liberal candidates in the next general election.

In his autobiography, Chretien endorses the King Doctrine wholeheartedly as he analyses the dissent which began to erupt within the Liberal Party in March 2000:

“If there was a conspiracy afoot, I figured it would backfire badly. There was no mechanism to oust me until after another election; there had been no resignations from Cabinet or uprisings in the party, except when John Nunziata voted against the 1996 budget and was expelled from caucus; and [Finance Minister] Martin wasn’t strong enough to orchestrate a coup.”[23]

By the second sentence, Chretien meant that only a leadership review at the biennial party conference could force him to resign. He also argued the Liberal parliamentary party could only have ousted him if they had voted against him on division on a key government bill or on a motion of confidence in the House of Commons itself, and not internally as a parliamentary party. But even then, Chretien makes clear that if the Liberal parliamentary party had rebelled, he would have responded by advising the Governor General to dissolve a majority parliament in which no other party could form government, and he would continue leading the Liberal Party in the snap election and probably win, only cementing his hold on power.

“In the parliamentary system, a prime minister remains prime minister until he is defeated in the House. […] As a result, whenever Martin’s supporters in the Cabinet and the caucus vehemently opposed any of my major decisions, I simply had to hint that I was ready to lose the vote in the House of Commons to make them either rally to my side or absent themselves with a strategic trip out of town. If the government had fallen on a serious matter, they knew, I would have called a quick election and been almost certain to win another five-year mandate.”[24]

Chretien recounts that he had originally planned on retiring around late 2000 or early 2001, in other words toward the close of the 36th Parliament elected in 1997, but that he and his wife decided on 18 March 2000 during the Liberal Party’s biennial convention in Ottawa that he would stay on to lead the party through one more election.[25] On 25 September 2000, Stockwell Day, the new Leader of the Opposition and Canadian Alliance, gave Chretien the opportunity to make good on his pledge. He taunted Chretien in the House of Commons and dared him to call an early election. “I almost crossed the floor to kiss him,” Chretien wrote in his memoirs. “He could hardly blame me for calling one after three and a half years when he himself had demanded it.”[26] After leading the Liberals to a big majority in November 2000, Chretien claims that he had then planned on announcing his retirement in November 2002 for a Liberal leadership convention in the fall of 2003, but Paul Martin’s faction within the Liberal Party “started to infect the harmony of the caucus, the solidarity of the Cabinet, and eventually the operation of the government.”[27]

In late May 2002, Paul Martin mused with reporters, “Will my continuation in the Cabinet, given these events, permit me in fact to exercise the kind of responsibility and influence that I believe a minister of finance ought to have?”[28] Chretien called Martin’s bluff and telephoned him to say that he “had accepted his resignation.” [29] For his part, Martin provided a different explanation in his memoir and claimed that he “got quit” by Chretien.[30] According to Martin, Chretien’s advisor Eddie Goldenberg called him and said that he must pledge an oath of fealty and prostrate himself before the media that he “intend[ed] to stay in the government.” Martin refused to sign a letter of resignation that Goldenberg had drafted calling the resignation a “mutual agreement” and wanted instead to make his own announcement the next day. In Martin’s account, Chretien still called his bluff but never said over the telephone, “I have accepted your resignation”; instead, Martin recounts that he had learned of his firing while driving to Ottawa and listening to CBC Radio’s Cross Country Checkup.[31]

How the Fallout of the Election in 2000 Fractured the Canadian Alliance and Spawned the Reform Act

Canadian political parties in opposition have forced their leaders to resign, either immediately or a few months later after holding a leadership convention. In 1983, Joe Clark convened a leadership convention after winning the support of only two-thirds of the Progressive Conservative Party in a scheduled leadership review; the parliamentary party did not force him to resign in this case, but he had to resign after losing the support of the party delegates to Brian Mulroney.[32] In contrast, the Liberals forced Stephane Dion to resign as party leader in December 2008 immediately after the proposed Liberal-New Democratic coalition fell apart and then swiftly acclaimed Michael Ignatieff as their new leader.[33] The Conservative Party pressured Andrew Scheer to resign shortly after the election of 2019, even though the Conservatives had won the plurality of the popular vote and reduced the Liberals to a plurality. The Conservative parliamentary party voted to oust Erin O’Toole as leader on 2 February 2022 under the Reform Act, after the election of 2021 produced virtually the same result as that of 2019.

But perhaps the most dramatic and drawn out example came in the aftermath of the snap election in 2000, which Stockwell Day, leader of the Canadian Alliance and Official Opposition, had dared Prime Minister Chretien to call and then lost badly. Chretien led his Liberals to a large parliamentary majority on par with what they secured in 1993. Naturally, these events caused some Canadian Alliance MPs to question Day’s judgement. The aftermath of the 2000 election also set the pattern which the Conservative Party of Canada, the successor to the Canadian Reform-Conservative Alliance, has inherited: new leaders boast that they can form government in their first general election, fail to achieve that goal, and then get ousted.

In early May 2001, several Canadian Alliance MPs had begun to question Stockwell Day’s leadership over the party’s poor performance in the general election the previous autumn. In the grand Canadian tradition of zero tolerance for any dissent, Day ousted Art Hanger from the parliamentary party for having questioned his judgement.[34] Party stalwarts Deborah Grey and Chuck Strahl then rebelled.[35] By July, 11 MPs had left the Canadian Alliance and formed a breakaway Democratic Representative Caucus (DRC).[36] On 9 July, Stockwell Day made an absurd offer to take leave of absence as leader of the Canadian Alliance until the party’s scheduled convention and leadership review in 2002, which the dissident MPs rejected.[37] Day then withdrew the offer and espoused the King Doctrine to the full, arguing that the parliamentary party could not oust him as leader: “The grassroots elected me. The grassroots and the [Alliance] constitution will determine my future.”[38] Day articulated the King Doctrine even more clearly in an interview with historian Bob Plamondon:

“The split-away group wanted me to step down, which was not a democratic response. When you are committed to democratic values you can’t allow yourself to be overrun by what appears to be a lack of respect for democracy. […] Had I stepped down, caucus would have disintegrated. The majority in caucus did not want me to step down. […] Let’s have a leadership race and that will carry us forward. It will settle things down and we will avoid tearing the party apart.”[39]

Day here argues that allowing the parliamentary party alone to elect and oust leaders is fundamentally anti-democratic; Day believed that “it was up to the party members, not caucus, to choose the party leader.” In August 2001, the DRC then entered into negotiations with Joe Clark’s Progressive Conservative Party; 8 DRC MPs then announced on 10 September 2001 that they would enter into a coalition with the PCs in opposition, which gave this new formation 20 MPs in total.[40] This story suffered the misfortune of appearing in the morning papers on 11 September 2001 and quickly escaped everyone’s notice until the House of Commons resumed sitting on 24 September, when Speaker Milliken acknowledged the “PC/DR Coalition” as a grouping but withheld “full party recognition” because it “is clearly an amalgam of a party [the Progressive Conservative Party] and a group of independent MPs.”[41] In other words, for practical purposes, the Speaker recognised the PC/DR Coalition merely a new guise of the Progressive Conservative Party and kept all the party rankings and committee memberships intact. Stockwell Day agreed to resign as leader of the Canadian Alliance in January 2002 so that the party could hold a new leadership election, in which Day still ran, along with Diane Ablonczy, Grant Hill, and Stephen Harper.[42] The PC/DR Coalition fell apart in April 2002 when Stephen Harper won the leadership of the Canadian Alliance.[43] Stockwell Day’s refusal to recognise the authority of the parliamentary party forced the Canadian Alliance to spend the better part of 18 months without an effective leader during which it failed to hold the Chretien ministry to account in the House of Commons.

The power of the near-invincible party leader now only insulates him for being ousted but allows him, in turn, to oust other MPs from the parliamentary party as punishment for personal misconduct, legitimate disagreements over policies, or for questioning the leader. Stockwell Day ousted Art Hanger for having questioned him. In November 2004, Paul Martin kicked Carolyn Parrish out of the Liberal parliamentary party in a minority parliament after she had called Americans “bastards,” ritualistically stomped on a doll of President George Bush, mocked the countries which joined the War in Iraq as “coalition of idiots,” and dismissed Martin himself as “weak.”[44] Stephen Harper kicked Garth Turner out of the Conservative parliamentary party in the next minority parliament in October 2006 for having divulged confidential caucus discussions on his blog, despite heading a tenuous single-party minority government at the time.[45] But Turner himself said that Harper kicked him out more for his outspoken views and criticism of the Harper ministry and not because he had divulged confidential internal discussions.[46] Turner sat as an independent for a few months before joining the Liberals in February 2007.[47] Erin O’Toole exacted this punishment on Senator Batters in late 2021 after she questioned his leadership.

The Reform Act Pushes Back Against Invincible Party Leaders

In April 2014, Conservative MP Michael Chong tabled the legislation which became the Reform Act in June 2015.[48] But Chong had to accept significant amendments to his bill, which nearly gutted it, in order to secure its passage. Originally, the bill would have added five procedures to the Parliament of Canada Act which outlined how recognised parties in the House of Commons could conduct leadership reviews, oust their leaders and appoint an interim leader, remove members from the parliamentary party, and re-admit said members to the parliamentary under some conditions. These provisions would have applied automatically to all parliamentary parties as a matter of course, like any normal statutory provision. But the Reform Act as enacted in 2015 made all these procedures contingent instead: every parliamentary party has to decide when it first meets after each general election whether to subject itself to each of the procedures, separately, and the decision applies only for the life of that particular parliament. In other words, in any given parliament, only some of these procedures might apply to some political parties, but they would not automatically apply universally. And if adopted, these procedures would only apply for a variable amount of time, because some parliaments last longer than others. Furthermore, this optional hodgepodge has become difficult if not impossible to enforce legally; despite being codified in a statute, these provisions have become merely politically enforceable, as if they were constitutional conventions.

In its first meeting after each general election, each parliamentary party must (but under no pain of true enforcement) vote on whether to apply each of these five procedures to itself for the duration of each parliament:

- Section 49.2: That a member of the House of Commons can only be expelled from the parliamentary party if at least 20% of the members of the parliamentary party ask that the caucus chair hold a vote to review the other member’s status, and if a simple majority of the parliamentary party votes by secret ballot to expel that member;

- Section 49.3: That a member of the House of Commons so expelled under that procedure can only become a member of that parliamentary party again by being re-elected as a candidate of that party, or if at least 20% of the members of the parliamentary party ask the caucus chair hold a vote to review the other member’s status, and if a majority of the parliamentary party then votes by secret ballot to re-admit that member;

- Section 49.4: The parliamentary party by secret ballot elects from amongst its members a caucus chair, who can only be removed if at least 20% of the parliamentary party deliver written notice to that effect, and if a majority by secret ballot then vote to oust said caucus chair;

- Section 49.5: The parliamentary party can initiate a “leadership review” by secret ballot “to endorse or replace the leader of a party” if at least 20% of its members sign a written notice to that effect. If a majority of the parliamentary party then votes to oust their leader, the caucus chair then presides over a second vote to elect an “interim leader” until the party holds its formal leadership election amongst its broader membership at one of those daft conventions.

- Section 49.6: The parliamentary party shall elect an “interim leader” as soon as possible under the procedure outlined in section 49.5 if the leader dies in office, becomes incapacitated, or resigns.[49]

The procedures in 49.2 and 49.3 are counted in the same vote, which is why a parliamentary party votes on whether to adopt four procedures under the Reform Act. So far, these procedures could have applied to the three parliaments elected in 2015, 2019, and 2021. But the details become hazy. Only the Conservative parliamentary party has ever voted to apply any of the procedures to itself, perhaps because the other political parties seem to regard this legislation as an attempt to change the Conservative Party’s procedures through a higher authority – not an entirely unfair criticism. The Liberal parliamentary party declined in the 42nd, 43rd, and 44th Parliaments to apply the provisions of the Reform Act to itself, which gave Trudeau the latitude to exact internal punishments unilaterally, or to pressure Liberal MPs to resign from caucus.

For example, Trudeau unilaterally ousted both Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott from the parliamentary party in 2019, even though they had resigned from cabinet before criticising him publicly.[50] Philpott raised a point of privilege and argued that Trudeau violated the terms of the Reform Act by ousting her from the parliamentary party unilaterally, but Speaker Geoff Reagan ruled against her, if only because he found that the Speaker could not adjudicate on matters with take place in caucus.[51] The best view is probably that the Liberal parliamentary party failed to abide by the terms of the Reform Act after the election of 2015 when Liberal MPs did not hold a recorded vote at all in their first caucus meeting on whether to apply the terms of the act to themselves for the duration of the 42nd Parliament.[52] Neither did the New Democrats. And since the Liberals did not even vote on whether to apply the Reform Act to themselves for the 42nd Parliament, elected in 2015, Trudeau remained free to oust MPs unilaterally. In 2019, the Liberal parliamentary party seems to have held the proper vote but declined to apply the Reform Act to itself for the 43rd Parliament.[53]

In the current parliament elected in September 2021, only the Conservative parliamentary party decided to subject itself to all four elements of the Reform Act.[54] The New Democrats and Blocists decided not to adopt any of the terms of the legislation, and the Liberals likewise unanimously rejected all provisos.[55] The Conservative parliamentary party ousted Derek Sloan from caucus using the provision under the Reform Act on 20 January 2021 during the 43rd Parliament. All these examples show that the Reform Act has become in some ways unenforceable outside of each parliamentary party, since no one can truly compel a parliamentary party to hold the vote on whether or not to apply these procedures to itself.

Conclusion

The Parliament of Canada has through the Reform Act presumed to “grant” members of parliament and a parliamentary party an authority to select and oust their party leaders which they already always possessed by necessity and by ancient parliamentary right. And yet, in practice, parliamentary parties probably needed this statute to reassert this old authority which nearly a century of electing party leaders by delegated conventions or directly by the party membership had put into desuetude and nearly extinguished altogether. Parties cannot easily rely on the authority of a tradition which has virtually died out. The Reform Act has so far failed to destroy the King Doctrine of the semi-invincible prime minister, and Canadian politicians themselves from all the major parties usually act as if the Prime Minister of Canada can only resign after his party clearly loses a general election and not because the parliamentary party or cabinet wants to oust him and select a new leader. Yet it seems also to fractured what until recently seemed like an impenetrable fortress.

The current iteration of the Reform Act will only succeed when the parliamentary party which has formed government decides to apply it to itself. Alternatively, Parliament could enact Michael Chong’s Reform Act in its original form, which would have applied the five procedures under the Parliament of Canada Act to all recognised parliamentary parties automatically and permanently instead of making them contingent on each parliamentary party voting to apply them to itself for the duration of one parliament at a time. But in practical terms, a parliamentary party can oust a leader without the Reform Act and irrespective of whatever the political party’s constitution says, because the constitutional conventions and practical realities of our system of government supersede whatever political parties presume to decree.

Similar Posts:

- Dissenting Liberal MPs Fail to Thatcher Trudeau (October 2024)

- Replacing the Prime Minister During an Election: A Forgotten Canadian Precedent (June 2024)

- A Mature Country Does not Demand Absolutist Party Discipline (February 2023)

- The Disgrace of Boris Johnson (February 2022)

- Bowden. J.W.J. “Party Discipline and Its Fate: Canada’s Ironclad Controls Are Beginning to Rust.” The Dorchester Review 12, no. 2 (2022): 47-58.

Notes

[1] John Paul Tasker, “A Defiant Trudeau Says He’s Staying on as Leader After Caucus Revolt,” CBC News, 24 October 2024; Bill Curry, “Trudeau Says He Will Lead Liberals in Next Election After Caucus Meeting on His Future,” The Globe and Mail, 24 October 2024; Terry Newman, “Trudeau Struts, Liberal Plotters Sit Down: The Prime Minister Isn’t Ready to Take a Walk in the Leaves,” The National Post, 24 October 2024.

[2] CTV News, “‘We Have to Process This’: Liberal MP Ken Hardie on Caucus Meeting,” 23 October 2024.

[3] Catherine Cullen, “At Least 24 Liberal MPs Tell Trudeau to Step Aside in Face-to-Face Meeting,” CBC News: Power and Politics, 23 October 2024.

[4] Abbas Rana and Ian Campbell, “B.C. Liberal MP Weiler Read a Letter to Trudeau and Caucus on Behalf of Dissenting MPs, Calling for the Prime Minister’s Resignation,” The Hill Times, 24 October.

[5] Ian Campbell and Abbas Rana, “Liberal Caucus Should Have Adopted Reform Act Process to Oust Trudeau, Says MP Casey,” The Hill Times, 24 October 2024.

[6] Ian Campbell and Abbas Rana, “Liberal Caucus Should Have Adopted Reform Act Process to Oust Trudeau, Says MP Casey,” The Hill Times, 24 October 2024; Ian Campbell, “Liberal Caucus Votes Unanimously Against Reform Act Measures,” The Hill Times, 11 November 2021.

[7] Bill Curry, “Trudeau Says He Will Lead Liberals in Next Election After Caucus Meeting on His Future,” The Globe and Mail, 24 October 2024

[8] Sean Casey, interview at 0:30 in “Trudeau Says He’s Staying On As Leader Despite October 28 Deadline Set by Dissenting MPs,” CBC News: Power and Politics, 24 October 2024

[9] Ian Campbell and Abbas Rana, “Liberal Caucus Should Have Adopted Reform Act Process to Oust Trudeau, Says MP Casey,” The Hill Times, 24 October 2024.

[10] Privy Council Office, “Tenth Ministry: 12 October 1917 – 10 July 1920,” Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 31 April 2017).

[11] The Globe, “Working Out the Details for Election New Interests: Understanding Reached Is There Shall Be No Distinction Between Liberal and Conservative Candidates Supporting the Union Government,” 13 October 1917, page 3.

[12] John W. Lederle, “The Liberal Convention of 1919 and the Selection of Mackenzie King,” The Dalhousie Review volume 27, no. 1 (April 1947): 86.

[13] J. L. Findlay and D.N. Sprague, The Structure of Canadian History, 6th ed. (Prentice-Hall, 2000), 363-364.

[14] Lederle, “The Liberal Convention of 1919 and the Selection of Mackenzie King,” 92.

[15] Rand Dyck, Canadian Politics: Critical Approaches, 6th ed. (Toronto: Nelson, 2011), 356.

[16] Audrey O’Brien and Marc Bosc, “Appendix 12: General Election Results Since 1867,” in House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 2nd Edition (Ottawa: House of Commons, 2009), 1274-1275.

[17] John W. Lederle, “The Liberal Convention of 1919 and the Selection of Mackenzie King,” The Dalhousie Review volume 27, no. 1 (April 1947): 86.

[18] Lederle, “The Liberal Convention of 1919 and the Selection of Mackenzie King,” 86.

[19] John C. Courtney, The Selection of National Party Leaders in Canada (Toronto: Macmillian Company of Canada, 1973), 128; Peter Aucoin et al., Democratising the Constitution: Reforming Responsible Government (Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications, 2011), 115.

[20] Barry K. Wilson, “Sir Mackenzie Disembowelled: The 1896 Cabinet Coup,” The Dorchester Review 9, no. 1 (Summer 2019): 22-28.

[21] Barry K. Wilson, Sir Mackenzie Bowell: A Prime Minister Forgotten by History (Loose Canon Press, 2021), 2.

[22] CBC News Archives, “Jean Chretien’s Long Goodbye,” 22 August 2002; BBC News, “Canada’s PM Sets Resignation Date,” 22 August 2002.

[23] Jean Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister (Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2007), 257.

[24] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 382.

[25] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 258-259.

[26] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 279.

[27] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 377.

[28] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 379.

[29] Chretien, My Years as Prime Minister, 379.

[30] Paul Martin, Hell or High Water: My Life In and Out of Politics (McClelland & Stewart, 2008), 235-236.

[31] Martin, Hell or High Water, 336.

[32] CBC Archives, “Joe Clark’s ‘Gutsy Political Move,’” 28 January 1983.

[33] Michael Valpy, Daniel Leblanc, and Jane Taber, “Ignatieff Makes His Move,” The Globe and Mail, 8 December 2008.

[34] Brian Laghi, “Alliance MP Defies Gag Order to Offer Support for Hanger,” The Globe and Mail, 4 May 2001.

[35] Deborah Grey, “Why We Need a New Leader,” The Globe and Mail, 11 June 2001.

[36] Bob Plamondon, Full Circle: Death and Resurrection in Canadian Conservative Politics (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2006), 22-23, 215-219.

[37] Brian Laghi, “Day Withdraws Offer to Resign,” 9 July 2001.

[38] CBC News, “Day Cancels Offer to Quit, Rebel MPs Blamed,” 9 July 2001.

[39] Plamondon, Full Circle, 216.

[40] CBC News, “Rebels Dump Alliance, Form Coalition with Tories,” 11 September 2001. The CBC posted this news article online at 12:39 am on 11 September, but they must have first received word of the news late on 10 September. Plamondon, Full Circle, 217.

[41] Peter Milliken (Speaker of the House of Commons), “Points of Order: PC/DR Coalition – Speaker’s Ruling,” 5489-5492, in House of Commons Debates, 37th Parliament, 1st Session, volume 137, no. 84, Monday, 24 September 2001, at 5492.

[42] Plamondon, Full Circle, 218.

[43] Brian Laghi, “Six MPs Head Back to Alliance,” The Globe and Mail, 11 April 2002.

[44] CBC News, “Parrish Kicked Out of Liberal Caucus,” 18 November 2004.

[45] Bill Curry and Alex Dobrota, “Troubles Grip Tories,” The Globe and Mail, 19 October 2006.

[46] Scott Deveau, “Turner Calls Tory Caucus Suspension ‘Unfortunate’”, The Globe and Mail, 18 October 2006.

[47] Scott Deveau, “Turner Says Party Time Should Be Over,” The Globe and Mail, 14 November 2006; Gloria Galloway, “Turner Defends Decision to Join Liberals,” The Globe and Mail, 7 February 2007.

[48] An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and the Parliament of Canada Act (candidacy and caucus reforms), Statutes of Canada 2015, chapter 37.

[49] An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and the Parliament of Canada Act (candidacy and caucus reforms), SC 2015, c. 37, at section 4.

[50] Marie-Danielle Smith, “Did Trudeau Break the Law by Expelling MPs?”National Post, 10 April 2019, A4.

[51] Marie-Danielle Smith, “Speaker Says MPs’ Ouster Not a Breach,” National Post, 12 April 2019.

[52] Andrew Coyne, “Clean, Quick Caucus Coup Less Bloody,” National Post, 5 November 2019, A4.

[53] Joan Bryden, “Liberal MPs Take Pass on Caucus Power,” National Post, 12 December 2019.

[54] Ian Campbell, “NDP and Bloc Caucuses Vote Not to Adopt Reform Act Measures,” The Hill Times, 22 October 2021.

[55] Ian Campbell, “Liberal Caucus Votes Unanimously Against Reform Act Measures,” The Hill Times, 11 November 2021.

Late to the party, as I am so often, but it’s an important point and a useful historical perspective.

Like so many of the things that Eugene Forsey termed “the rot in our national life”, this Law of the Hyper-Whipped Caucus seems to have started with WLM King. Now it seems every political party wants to show off a leader “elected” by the party membership, . The message is ex partia non est salus; you want a say in how your country’s governed, then either join us or wander in the wilderness. That leads to brokerage parties and a spoils system, not to representative democracy.

I echo Mark R’s sentiment about what is/isn’t “democratic” in leadership matters. I made my views indecently plain here:

https://www.smalldeadanimals.com/2013/12/03/as_canadians_fr/#comment-1050393

and here:

https://godscopybook.blogs.com/gpb/2014/09/with-friends-like-these.html?cid=6a00d834

And today the Murrican magazine Foreign Policy is stuck on stupid about the same question, so I sent them a rocket:

https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/19/justin-trudeau-canada-resignation-chrystia-freeland/

LikeLike

“Day here argues that allowing the parliamentary party alone to elect and oust leaders is fundamentally anti-democratic”

I would personally argue the opposite. MPs are all elected with individual democratic mandates. Binding them to never question the party’s internal choice of leader is what would be anti-democratic. Elections do not annoint parties to represent the people. They elect 338 individuals to represent the people.

LikeLike