Introduction: Readjusting Federal Electoral Boundaries

Section 51(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867 requires that the number of MPs per province be recalculated after each decennial census and, consequently, that the electoral boundaries of ridings within each province be readjusted every ten years. Parliament redrew electoral boundaries directly from the 1870s to the 1950s. But since 1964, the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act provides that independent Federal Electoral Boundaries Commissions, one for each province, decide where and how to readjust electoral boundaries in a non-partisan manner. Each commission is chaired by a judge and consists of two other members appointed by the Speaker of the House of Commons. The commissions release an initial proposal, hold public hearings throughout the province on that proposal, and then release a preliminary report based on what they learned from anyone who commented either for or against the proposal. MPs then study the preliminary reports and make recommendations on changing either the names or boundaries of ridings, which the commissions must consider but may (and usually do) reject in their final reports. Those final reports then become the Representation Order, a piece of secondary legislation that the Governor-in-Council promulgates under the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act. Those Representation Orders enter into force for a dissolution of parliament seven months later.

In 2021, the Chief Electoral Officer published the calculation on section 51(1), which showed that the House of Commons increased overall from 338 to 343, with Alberta having gained three new MPs and British Columbia and Ontario each having gained one. The Federal Electoral Boundaries Commissions for each of the ten provinces began their work on 9 February 2022 when Statistics Canada released the population and dwelling counts for each province and each of the 335 provincial ridings established under the previous electoral redistribution in 2013, and they completed their work at various points from late 2022 to mid-2023. The Governor-in-Council issued the Representation Orders, 2023 on 23 September 2023 as part of the Proclamation Declaring the Representation Orders to be in Force Effective on the First Dissolution of Parliament that Occurs after April 22, 2024. Consequently, 23 April 2024 marked the first day after 22 April 2024 and when the new federal electoral boundaries entered into force to apply in the next general election – whenever that happens.

As of 2024, nine of the ten provinces have enacted legislation providing that some sort of electoral boundaries commission readjusts the boundaries of electoral districts must automatically take place every eight to twelve years, or after every second or third general election, to account for shifts in population. This automatic periodicity guarantees that each MLA (or MPP, MHA, or MNA) represents roughly either the same number of people or the same number of electors (this metric depends on the province) within variances that range from ±5% in Saskatchewan to ±10% in Newfoundland & Labrador and in southern Manitoba, ±15% in New Brunswick, and ±25% in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Ontario stands up as a bizarre and notable exception as the only province which has never adopted a comprehensive law to make electoral boundaries readjustment automatic every x number of years or after every x number of general elections. This leads directly into what Doug Ford said last week.

The Press Conference That Started It All

Doug Ford, Premier of Ontario since 2018, started this controversy at the end of a news conference in Oshawa where he announced the construction of a new hospital in Whitby and improvements to healthcare across the region of Durham.[1] The following exchange began at 20:08 and concluded at 21:36:

Morris: Siobhan Morris from CTV News.

Ford: Hi, Siobhan.

Morris: Will you be realigning the provincial riding boundaries to match – ?

Ford: No.

Laughter

Morris: “No.” You didn’t even let me get it out! Can you explain why?

Ford: Because why change something that works? It works, so it’s all good. Just because the feds want to do it, [to] jerry-rig [sic] the ridings – and it’s no secret: people do that, governments do that. I’m not doing it. I’m going to leave the boundaries alone, and people will decide if they want to move forward with our government on prosperity, on healthcare, on the economy, or they want to go backwards and vote for the other guys. They’ll have that choice.

Morris: Is there a consideration there about keeping a lid on spending? Adding more members to the house? Is that a concern for you?

Ford: No, we’re just leaving it alone. We just aren’t touching the boundaries.

The less [sic] politicians, the better it is.

More canned laughter

Ford and his staffers neither anticipated nor understood that this back-and-forth would prove contentious or even become memorable at all; the main press release summarizing Ford’s speech touted “building a more connected healthcare system for Durham Region” and makes no mention of electoral boundaries.[2]

If Premier Ford wants to accuse the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario of having engaged in skullduggery and chicanery, he could at least muster the decency to say “gerrymander” properly instead of opting for “jerry-rig.” His utterances reveal that he knows nothing about how readjusting electoral boundaries works in Canada.

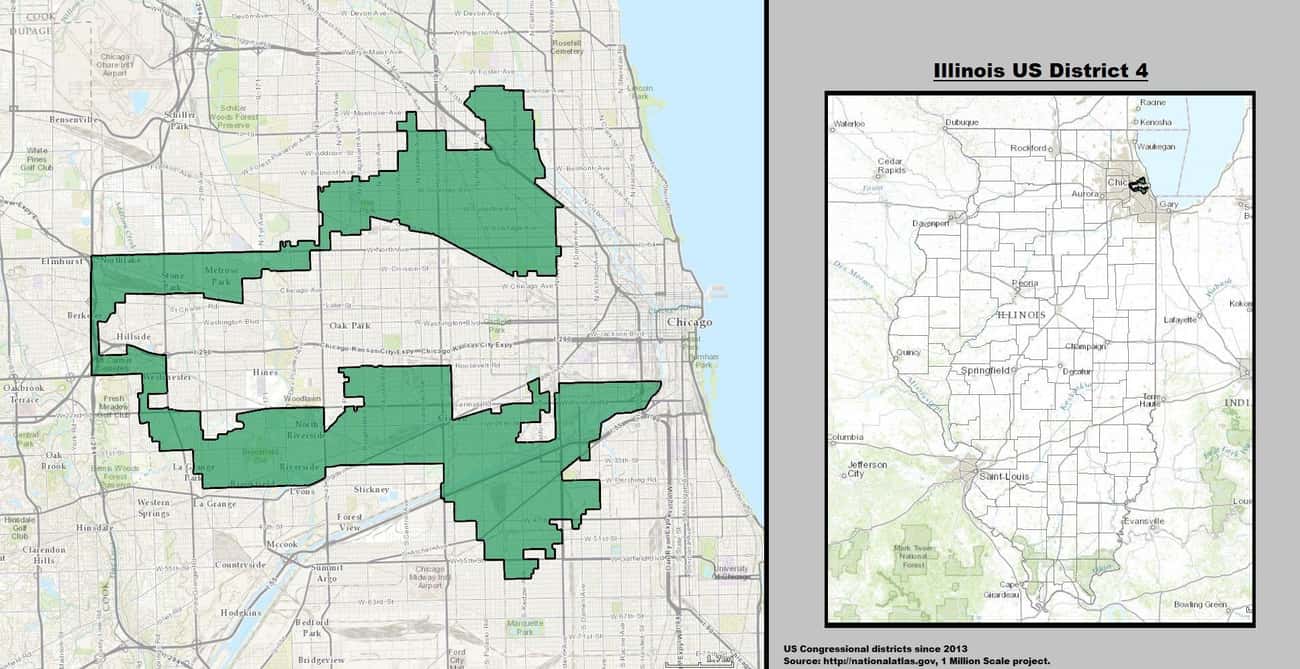

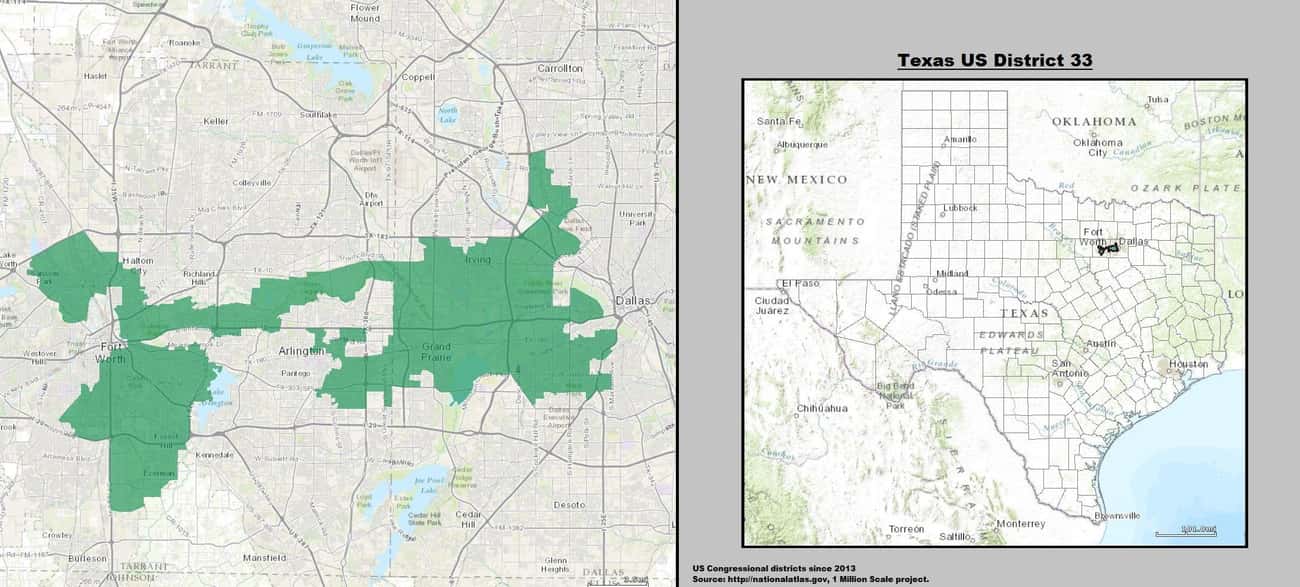

Gerrymandering means that the party in power manipulates the boundaries of electoral districts to maximize the votes of its own supporters and dilute the votes of its opponents in an attempt to consolidate its gains in subsequent general elections and stay in office for as long as possible. [3] This pattern held for the first century after Confederation in Canada and still holds sway in many American states today. Politicians crack and pack electoral districts, breaking up the pockets of support of their opponents and dispersing them across many districts while at the same time consolidating their supporters into one district. Since single-member districts cannot by definition overlap with one another, the most mathematically “compact”, or perfect, electoral district has only four sides. In contrast, a gerrymandered district suffers from low compactness and degenerates into an arbitrary, sprawling and multi-sided monstrosity which cobbles together many pockets of support for one political party.[4]

The infamous “Earmuffs District” in Illinois just barely remains contiguous but looks ridiculous and clearly suffers from horrendous gerrymandering.

Even Canadian federal electoral districts which appear at first place non-compact remain contiguous. Ridings like Thunder Bay–Rainy River also become less quadrilateral and more multi-sided because they follow the course of international or interprovincial borders, or bodies of water — which does not signify gerrymandering.

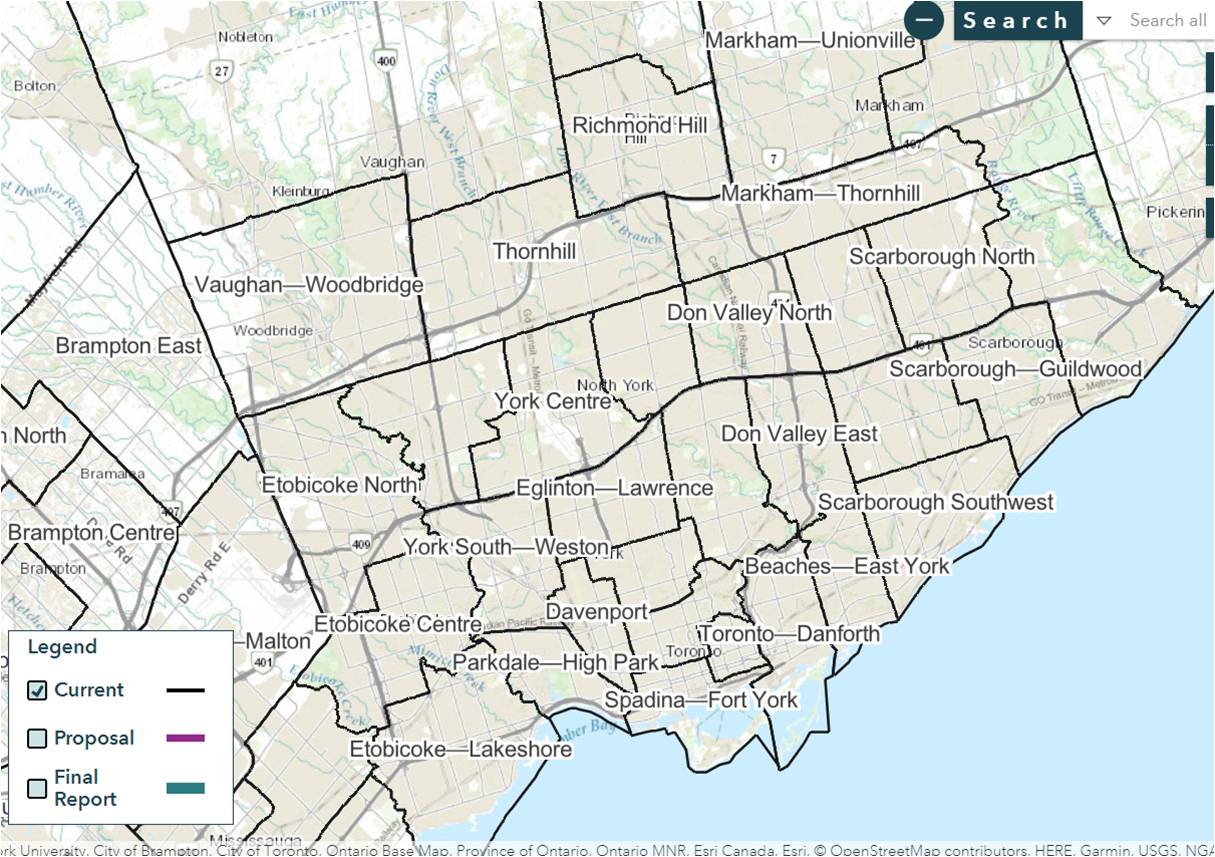

The ridings all roughly quadrilateral; where they gain more than four sides, it is because they follow either a major arterial road or highway which separates communities of interest, or a body of water like a creek or Lake Ontario itself.

Ideally, the electoral districts within a province would each contain roughly the same number of people within a narrow variance of the average number of people per MP and these districts would also be established without regard to political party and would instead follow the general geographic contours of the province as rough quadrilaterals. And if Doug Ford had ever looked at a map of electoral districts, he would have seen that most Canadian ridings meet that description. An independent electoral boundaries commission by definition does not rig or gerrymander. Furthermore, Ford also seems not to understand that Ontario only gained 1 new MP in the House of Commons under the Representation Order, 2023, going from 121 to 122. One additional MPP would neither inundate Queen’s Park nor significantly increase skullduggery there.

The Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario in its final report strongly condemned some of the idle commentary by MPs. This admonishment now applies equally to the Premier as well:

“False and misleading public statements by Members of Parliament such as the claim that there is ‘gerrymandering’ regarding the adjustment of Canadian electoral boundaries, or that the public is ‘disenfranchised’ by the process, undermine public confidence in democracy. Members of Parliament, especially, should not disparage democratic institutions because they do not give them the particular outcomes that they want.”[5]

Incidentally, Ford also strongly implied once more in that response that he will opt for an early dissolution well before the next general election scheduled under Ontario’s fixed-date elections law in June 2026. He desperately wants to hold an early provincial general election under the old electoral map before the next federal general election, given Ontarians’ tendency to vote for the opposite parties federally and provincially. Ford also therefore does not understand that Conservative Party of Canada stands to benefit most from Ontario’s new federal electoral boundaries because shifts in population forced the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario to take away one riding out of Liberal Toronto proper and put it in the competitive marginal constituencies of the western GTA.

But we need to look beyond these easy and obvious critiques of Doug Ford and understand that this problem goes well beyond him and extends back to at least the 1970s.

Ontario Went Ad Hoc: No Law Provides for Automatic Electoral Boundaries Readjustment

Ontario trundled through decades of ad hockery on readjusting electoral boundaries before Mike Harris trolled us all with his Fewer Politicians Act of 1996. Where Manitoba pioneered the Canadian model in the 1950s, which Ottawa later emulated in 1964, of enacting legislation providing that independent electoral boundaries commissions must revise the electoral map every decade or so, Ontario lagged behind. But Canada’s largest province refused to follow suit. Ontario’s Legislative Assembly instead adopted motions in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s to create commissions ad hoc but never enacted legislation to make sure that the Lieutenant Governor-in-Council would have to appoint a new electoral boundaries commission automatically every x number of years or after x number of general elections.[6] The Legislative Assembly therefore retained closer control of this whole process than it should have and than the assemblies of other provinces did.

Mike Harris decided to cut the Gordian Knot in 1996 not by tabling a comprehensive bill to give Ontario its own independent provincial electoral boundaries commission but instead by trolling us all through Bill 81, The Fewer Politicians Act. This legislation, as its long title says, “reduce[d] the number of members of the Legislative Assembly by making the number and boundaries of provincial electoral districts identical to those of their federal counterparts.”[7] The consolidated form of this legislation reduced the size of Ontario’s Legislative Assembly from 130 to 103 MPPs, which the Legislative Research Service describes as “one of the largest reductions of a modern legislature on record.”[8]

The Representation Act, 1996 implemented this policy simply as follows:

Provincial electoral districts

- (1)For the purpose of representation in the Legislative Assembly, Ontario is divided into electoral districts whose number, names and boundaries are identical to those of its federal electoral districts.

One member per district

(2) One member shall be returned to the Assembly for each electoral district. 1996, c. 28, Sched., s. 2.

Effect of federal readjustment

- When there is a federal readjustment, new provincial electoral districts are deemed to be established in accordance with subsection 2 (1), in place of the existing provincial electoral districts that are affected, immediately after the first dissolution of the Legislature that follows the first anniversary of the proclamation date of the draft representation order under the federal Act. 1996, c. 28, Sched., s. 3.

Effect of federal change of name

- (1)If only the name of a federal electoral district is changed, the name of the corresponding provincial electoral district undergoes the same change at the same time.

Exception

(2) However, if the federal change of name takes place after a writ for an election is issued in the corresponding provincial electoral district, the provincial change of name does not take place until the day after polling day. 1996, c. 28, Sched., s. 4.[9]

Mike Harris’s legislation at least had the virtue of applying the latest Representation Order promulgated under the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act automatically and without the need for any further intervention on the part of the Parliament of Ontario. This legislation applied Ontario’s federal electoral districts contained in the Representation Order, 1996 and the Representation Order, 2003 to Queen’s Park without incident.

The immediate problem that we face today originated in 2005 with Dalton McGuinty’s legislation. The Representation Act, 2005 bifurcated Ontario to stop the North from losing ridings upon each federal electoral redistribution while still making Ontario’s federal electoral districts the provincial electoral in the rest of the province. The new legislation guaranteed Northern Ontario a minimum of 11 ridings at Queen’s Park and then applied the federal “southern electoral districts” to the rest of the province. In other words, this legislation modified the boundaries contained in the Representation Order, 2003 after the fact with respect to Ontario’s provincial electoral districts in the North.

Redistribution

- (1)For the purpose of representation in the Legislative Assembly, Ontario is divided into the following electoral districts:

1. The 11 northern electoral districts listed in section 4, with the same boundaries as were in effect on October 2, 2003, subject to subsection (2).

2. In the part of Ontario that lies outside the 11 northern electoral districts, 96 southern electoral districts whose names and boundaries are identical to those of the corresponding federal electoral districts, subject to subsection (3). 2005, c. 35, Sched. 1, s. 2 (1).

Unfortunately, this new section 2 no longer allowed the “southern electoral districts” for Ontario’s Legislative Assembly to update automatically after the entry into force of each new federal representation order. The provincial parliament probably reverted to the ad hockery out of necessity because a Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario could always end up changing the northern boundaries of those “southern electoral districts,” given that its authority flows from the federal Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act and not any provincial statute. That is not a risk that Ontario’s Parliament could take. Consequently, the provincial parliament needs to review every new federal representation order and then apply it manually through new legislation after each representation order.

The Wynne government conducted this manual review in what became the Representation Act, 2017, which applied ad hoc the Representation Order, 2013 to “111 southern electoral districts” and guaranteed Northern Ontario a fixed number of 13 ridings instead of 11.

Redistribution

2 (1) For the purpose of representation in the Legislative Assembly, Ontario is divided into the following electoral districts:

1. The 13 northern electoral districts, whose names and boundaries are set out in the Schedule.

2.In the part of Ontario that lies outside the 13 northern electoral districts, 111 southern electoral districts whose names and boundaries are identical to those of the federal electoral districts that come into effect on the first dissolution of Parliament after May 1, 2014. 2017, c. 18, s. 1 (1, 2).[10]

The Province of Ontario made the northern boundaries of the federal electoral districts of Bruce Grey—Owen Sound, Simcoe North, Haliburton—Kawartha Lakes—Brock, and Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke the main dividing line between Northern Ontario (where electoral districts could become different) and Southern Ontario (where the province adopted all the federal electoral districts as its own). The federal and provincial Parry Sound—Muskokas looks very similar, but they must contain some differences because the Representation Act, 2015 of Ontario lists it in the schedule as a distinct northern riding.

Consequently, if the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario changed the northern boundaries of any of the four aforesaid federal electoral districts (Bruce Grey—Owen Sound, Simcoe North, Haliburton—Kawartha Lakes—Brock, and Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke), then the Parliament of Ontario could not simply enact legislation declaring that the 113 southern federal electoral districts shall also count as 113 southern provincial electoral districts, because then some parts of the province would fall under two sets of electoral districts, both the 13 northern electoral districts under the Representation Act, 2017 and the 113 southern electoral districts under a hypothetical Representation Act, 2024. That simply cannot happen under single-member plurality, where all parts of the province must fall exclusively in only one geographic electoral district represented by one MPP.

Thankfully, the Map Viewer on the website for the federal Redistribution 2022 shows that the northern boundaries of these four crucial electoral districts (Bruce Grey—Owen Sound, Simcoe North, Haliburton—Kawartha Lakes—Brock, and Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke) have, mercifully, remained intact under the Representation Order, 2023 relative to the previous Representation Order, 2013. Consequently, the Parliament of Ontario could both keep the 13 northern provincial electoral districts established under the Representation Act, 2017 intact and also adopt the federal electoral boundaries for the 113 electoral districts south of these areas. The Ford government therefore should introduce legislation that would amend section 2(1)(2.) of the Representation Act, 2015.

The new bill could therefore say the following:

Redistribution

2 (1) For the purpose of representation in the Legislative Assembly, Ontario is divided into the following electoral districts:

- The 13 northern electoral districts, whose names and boundaries are set out in the Schedule.

- In the part of Ontario that lies outside the 13 northern electoral districts, 113 southern electoral districts whose names and boundaries are identical to those of the federal electoral districts that come into effect on the first dissolution of Parliament after April 22, 2024.

Effective date

(2) The redistribution described in subsection (1) takes effect immediately after the first dissolution of the Legislature after the date on which this bill receives Royal Assent.

However, this would, in my opinion, only provide another temporary, ad hoc fix to a broader problem. The Ford government should also accept the recommendation of the Chief Electoral Officer and table a bill to establish an automatic and periodic electoral boundaries commission for Ontario – which every other province has already long since done.

Ontario now layers ad hockery atop more ad hockery ad infinitum, ultimately because the Progressive Conservative Dynasty of 1943 to 1985, then Peterson’s Liberals of 1985 to 1990, and Rae’s New Democrats of 1990 to 1995 never bothered to adopt proper comprehensive legislation for a separate and independent electoral boundaries commission of Ontario. Harris fixed the problem in a way, but then McGuinty and Wynne interfered with a closed system without properly and comprehensively replacing it and therefore forced Ontario to revert back to more ad hockery. Ford’s Progressive Conservatives now face the same basic and structural dilemma, which Ford decided to compound by making ignorant utterances and falsely accusing the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario of having snuck through a gerrymander.

Ford blithely insisted that the Parliament of Ontario need not update the electoral boundaries in the majority of the province because “it” – the current electoral map from the 2010s – “works.” But Ford understands neither the origin nor the purpose of Ontario’s bizarre decision, unique amongst the 10 provinces, to tie most of its provincial electoral boundaries to the province’s federal electoral boundaries. The current electoral map does not “work” because it now contains massive disparities in population, even between ridings within the same region like the Greater Toronto-Hamilton Area, in contrast to the newest federal electoral boundaries which would smooth out those differences in population. But more importantly and fundamentally, the entire idea of basing the provincial electoral map on Ontario’s federal electoral districts no longer “works” and has become unfit for purpose.

Harris adopted this method to save money and time: Ontario both would pay fewer MPPs, and forego having to establish its own provincial electoral boundaries commission. However, since the Parliament of Canada adopted a new Representation Formula in 2011 that increased the number of MPs for Ontario from 106 to 121 in one fell swoop, this, in turn, increased the number of MPPs at Queen’s Park to only 9 fewer than in 1996. McGuinty and Wynne then rendered this method more moot by adding a handful of more MPPs to the North; as of 2024, the Legislative Assembly now sits 124 MPPs, or only 6 fewer than in 1996. McGuinty’s and Wynne’s legislation also stopped the automatic application of the latest federal representation order to Ontario, which means that we no longer save as much time as we did under Harris’s method. The legislative assembly must now debate the issue of electoral boundaries, and the provincial parliament must enact a new law separately every few years. In 2017, the Wynne government even went so far as to establish a Far-North Electoral Boundaries Commission that mimicked the normal process of readjusting electoral boundaries on small scale in part of the province. These amendments have layered on more complexity and produced the worst sort of system rife with arbitrariness and controversy, wherein each individual parliament has to consider whether to create an electoral boundaries commission and MPPs must implicate themselves and legislate electoral boundaries directly. Ontario should in principle control something as basic as how many MPPs represent its people independent of tethering that figure to what the federal order of government does and of how many MPs represent the province in the House of Commons.

The Disparities in Population Under Ontario’s Current Electoral Boundaries That Can Be Fixed

But what, concretely, does Ford’s refusal either to adopt the new federal electoral boundaries or provide a separate provincial electoral boundaries commission mean? David Moscrop and John Michael McGrath both mentioned the disparities in population in their columns but neither provided the details necessary to illustrate those disparities. They also both framed their critique of Ford in terms of equality of voters. I used to make this mistake myself until quite recently as well, so I’m not pointing out this distinction purely for the sake of pedantry, but because this common misnomer glosses over key differences between various provincial and federal statutes and theories of what political representation in legislative assemblies means. First of all, only the single-transferable vote of jurisdictions like Ireland, Malta, and Tasmania guarantees the equality of voters – which is to say, of those who cast valid ballots in any specific general election – because the Droop Quota uses the total number of votes cast to determine how many votes a candidate needs to win to get elected in a multi-member electoral district on a ranked ballot. So what they mean when they say or allude to the equality of “voters” is in fact the equality of electors, or what we might call eligible voters: adult Canadian citizens. Second, the various federal and provincial statutes differ on this question.

Those of Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec all calculate their electoral quotas based on the number of electors instead of their populations,[11] while the equivalent legislation in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario (which simply uses the federal electoral districts outside of the North), Manitoba, Alberta, and British Columbia all rely on the population as a whole in line with the federal model and thus seek the equality of population rather than “voter parity”, or, more accurately, the equality of electors.[12] Saskatchewan’s statute stands out as the lone exception for basing the electoral quota on the “total adult population,” at once narrower than the total population and broader than the number of electors. In the provinces which define their electoral quotas based on the number of electors per MLA (and therefore riding, since all provinces use single-member plurality), you could therefore make the case that MLAs only represent electors instead of all people. But in the provinces which define their electoral quotas based on the number of people per MLA, you would have to conclude that MLAs represent all people in their ridings. The federal Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, which Ontario has adopted, also defines the electoral quota as the average number of people per MP – not the number of electors.

I can show you precisely by the comparing two sets of numbers: the population and dwelling counts from the decennial census of 2021 under the electoral boundaries established in 2013 versus the populations of the new electoral boundaries based on the census of 2021 which entered into force in April 2024.

- 3. Loosemore-Hanby Index on the Representation Order, 2013

- 0. Loosemore-Hanby Index on Census of 2021 under the Rep Order, 2013

- 3. Loosemore-Hanby Index in the Representation Orders, 2023

What a contrast! Under the electoral map from the 2010s, the populations of 6 of the 121 electoral districts have exceeded the electoral quota by greater than 25% – the maximum allowance under the federal Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act – and 24 exceed the electoral quota by greater than 10%. Brampton West stands out as as the most disproportional by far; its population exceeds the electoral quota by fully 39.25%. In contrast, the adjacent riding of Brampton Centre comes in at -10.32% of the electoral quota. Other ridings within Toronto proper like Don Valley East come in at -18.48% of the electoral quota. This electoral map from the 2010s, which the ages have now skewed, registers at 5.18% on the Loosemore-Hanby Index compared to only 2.87% when the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario created it in 2013. (The closer to 0, the more proportional, and therefore better, the electoral map is).

But under the new electoral map for the 2020s, the populations of all ridings in the Western GTA fall below +10% of the electoral quota. This new map therefore provides a much fairer allotment and registers at 3.21% on the Loosemore-Hanby Index. One could make a strong case, as McGrath recently has in his aforesaid column, that the current electoral boundaries in the province of Ontario, flowing as they do from the federal electoral boundaries of the 2010s, have become disproportional enough that they violate the Doctrine of Effective Representation that the Supreme Court established in Carter in 1991.

Conclusion: Ontario Needs to Enact Its Own Electoral Boundaries Commission Act

During the pandemic, Doug Ford showed a propensity toward making rash utterances only to do an about-face once he understood the severity of the controversy that he caused and the backlash that he generated. So I would not be surprised if Ford ends up tabling legislation when the Legislative Assembly reconvenes on 21 October 2024 to apply the 113 federal electoral districts outside of northern Ontario established under the Representation Order, 2023 to the Province of Ontario as well – especially when some of his advisors and colleagues at Queen’s Park remind him that the new electoral boundaries probably benefit the federal Conservatives, and therefore perhaps the his own Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario. (But, I hasten to add, this potential benefit to the Conservatives has occurred by happenstance because of the decennial census of 2021 and the political climate of 2023-2024, not design and therefore not because of gerrymandering.) After all, the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario ended up taking away one riding from Toronto proper and moving it to the GTA and gave Ontario’s new riding to the western GTA as well. Eric Grenier has examined this question in exhaustive detail on The Writ; applying the results of the election in 2021, he concluded in mid-2023 that the new electoral map for the 2020s made favours the Conservatives in the southwest, north, and east of Ontario, while the Liberals could hold Toronto and Peel.[13] But irrespective of which federal political party stands to gain, we should readjust electoral boundaries every decade or so simply to preserve the principle that each MP should represent approximately the same number of people.

Various committees of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario and the Chief Electoral Officer of Ontario have recommended time and again to no avail since the 1970s that the provincial parliament adopt a new and comprehensive law on readjusting electoral boundaries. The Select Committee on Election Laws first did so in June 1970.[14] In 2005, the Select Committee on Electoral Reform pointed out matter of factly that if Ontario switched from single-member plurality to mixed-member proportional representation (with its mixture of single-member districts and compensatory party-list seats), the provincial parliament would quite simply have to “establish its own electoral boundaries commission.”[15] For instance, if Ontario has 124 ridings and MPPs under single-member plurality, but then switches to mixed-member proportional representation while keeping the same number of MPPs, some of those MPPs would become party-list MPPs, which would mean that the number of single-member districts decreases from 124 to 124 minus the number of party-list MPPs. And this, in turn, would completely decouple Ontario’s provincial electoral districts from its federal electoral districts and force the province to establish its own electoral boundaries commission.

In 2009, the Select Committee on Elections likewise considered that the provincial parliament establish a “permanent boundaries commission comprised of the Chief Electoral Officer, a Justice of the Ontario Superior Court, and an academic who will, using the co-terminus federal boundaries as a baseline, on a regular, established schedule, review any special requirements that the Province may have to ensure that the principle of effective representation of electors is respected.”[16] Incidentally, this wording would suggest defining the electoral quota as the average number of electors, rather than people, per MPP.

The Chief Electoral Officer of Ontario has repeatedly recommended that the provincial parliament adopt legislation on readjusting electoral boundaries regularly since at least 2015. Greg Essensa noted in 2015: “The Chief Electoral Officer has advocated for several years that the Representation Act, 2005 be amended to update and provide a regular, scheduled process for reviewing electoral districts and boundaries.”[17] He also lamented that “Ontario is the only province in Canada that does not have a regularly scheduled process for reviewing its electoral district boundaries.”[18] He reiterated his recommendation the next year: “The Chief Electoral Officer recommends that the Representation Act, 2015 be amended to provide a regular, scheduled process for reviewing the electoral districts and boundaries.” [19] He even put the original in bold italics in the vain hope that someone in the Premier’s Office would notice. Essena further argued that “As the only province in Canada without a regularly scheduled process, Ontarians face a greater risk of ineffective representation in our democratic institutions.”[20]

In 2017, the Chief Electoral Officer acknowledged the Far-North Electoral Boundaries Commission and the Representation Statute Law Amendment Act, 2017 which increased Northern Ontario’s fixed allotment from 11 to 13 ridings. Essena continued with this refrain in 2017 as well, even copy-pasting the wording of his own previous report though this time only in italics: “The Chief Electoral Officer recommends that the Representation Act, 2015 be amended to provide a regular, scheduled process for reviewing the electoral districts and boundaries.”[21] Finally, Essena pleaded once more than the parliament adopt proper, comprehensive legislation for a regular provincial electoral boundaries commission in his report on the 42nd general election; though as if giving up, he put this last plea neither in bold nor in italics: “Redistribution allows for effective representation. Elections Ontario recommends a regular, scheduled process for reviewing Ontario’s electoral district boundaries.” [22]

Ford has undoubtedly earned some of the mockery and scorn heaped upon him, but we should not allow his bizarrely ignorant remarks from 1 August 2024 to cloud the true problem that Ontario faces here: the ticklish business of readjusting electoral boundaries in Ontario extends back at least a half-century. Manitoba and Ottawa set the precedent that an independent commission should readjust electoral boundaries based on objective and open criteria in the 1950s and 1960s, and Ontario should have followed suit by at least the 1970s. Ford’s musings earlier this month flow from, rather than cause, the broader problem.

Ontario should accept the Chief Electoral Officer’s repeated recommendations. This province must definitively break with the legacy of Mike Harris’s trolling Fewer Politicians Act, 1996, and the subsequent poorly planned tinkering undertaken by McGuinty and Wynne, as well as the ad hockery of the 1960s to the 1980s. Quite simply, Ontario needs to enact its own legislation to create a provincial electoral boundaries commission. This legislation should decide how many MPPs should represent the people of this province overall, while preserving the slightly over-representation of the north. Saskatchewan would therefore provide the best model. Saskatchewan assigns 2 MLAs to its North, irrespective of population, but then provides that the populations of the 57 ridings in the South must come within ±5% of the electoral quota. Ontario could therefore continue to assign the North 13 MPPs irrespective of its population and then declare that the populations of the electoral districts in the South must come within ideally ±5%, or perhaps up to ±10%, of the electoral quota. The province would then, in turn, have to decide whether to define the electoral quota as the average number of people per MPP and riding, or, alternatively, the average number of electors per MPP and riding. The federal Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act defines the electoral quota as the average number of people per MP, and therefore Ontario currently uses that same standard. The legislation should establish the total number of ridings as 13 for the North and x-13 for the South. It could perhaps also adopt an electoral quotient similar to that contained in section 51(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867 for the federal House of Commons so that the number of MPPs can increase slowly over time, which, in turn, means that the total number of people or electors per MPP does not increase ad infinitum every decade but instead also rises more slowly.

The Parliament of Ontario needs to start taking this issue seriously and come up with legislation that makes any readjustment of electoral boundaries happen automatically every eight to ten years so that this question stops depending upon this arbitrary system where any individual parliament has to decide – or not decide – to carry out an electoral redistribution. This would also spare us all the spectacle of Doug Ford and any of successors showcasing as astounding ignorance of how readjusting electoral boundaries works in Canada. Ford believes that the fewer politicians the better. I would counter that the less politicians can interfere with readjusting electoral boundaries, the better.

Similar Posts:

- Electoral Boundaries Readjustments

- My Latest Article on Federal Electoral Boundaries Readjustment in the Canadian Parliamentary Review (May 2024)

- Out with the 338 and in the 343: The New Federal Electoral Boundaries Just Entered into Force Today! (April 2024)

- Bowden, J.W.J. “The Ever-Expanding House of Commons and the Decennial Debate Over Representation by Population.” Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law 17, no. 1 (2023): 85-122.

- The Gerrymander of 1882 (January 2024)

- British Columbia & Ontario Would Each Already Gain 1 MP (December 2023)

- The Canadian Study of Parliament Group’s Conference on “Dissecting Redistribution” (April 2023)

- Readjusting Electoral Districts in Federations: Malapportionment vs Gerrymandering (August 2022)

- A Response to the Broadbent Institute’s Polemic for Mixed-Member Proportional Representation (March 2016)

- CSPG Conference: Paul Dewar Dodged My Question on Section 52 and Over-Representing Quebec (October 2011)

- James W.J. Bowden, “Favouring Quebec in Parliament Is Unconstitutional,” National Post, 17 October 2011

- My Column in the National Post on the New Democrats’ Unconstitutional Private Members’ Bill to Give Quebec a Fixed Proportion of Seats (October 2011)

- The New Democrats’ Anti-Constitutional Stance on Electoral Redistribution (September 2011)

Notes

[1] Ontario, Office of the Premier, Media Advisory: Premier Ford to Hold a Press Conference, 31 July 2024.

[2] Ontario, Office of the Premier, News Release: Ontario Building a More Connected Health Care System for Durham Region, 1 August 2024.

[3] Nick Seabrook, One Person, One Vote: A Surprising History of Gerrymandering in America (New York: Pantheon Books, 2022), 4-5.

[4] Zack Taylor et al., “Canada’s Federal Electoral Districts, 1867-2021: New Digital Boundary Files and a Comparative Investigation of District Compactness,” Canadian Journal of Political Science (2023): 6.

[5] Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario, “Addendum to the Report: Disposition of Objections (July 8, 2023): Comment on Process or Procedural Issues,” in Final Report of the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario Published Pursuant to the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act (8 July 2023), at pages 253-254.

[6] Philip Kaye, “Redistribution of Electoral Districts in Ontario,” Ontario Legislative Library, September 1996, at pages 4-19.

[7] Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Bill 81, Fewer Politicians Act, 1996, 36th Parliament, 1st Session, 9 December 1996.

[8] Larry Johnson, “Frozen Districts: The Status of Electoral Redistribution in Ontario,” Legislative Research Service Research Paper 12-02, March 2012, at page 3.

[9] Representation Act, 1996, S.O. 1996, chapter 28, at sections 2-4.

[10] Representation Act, 2015, S.O. 2015, chapter 31, at section 2; as amended by Representation Statute Law Amendment Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 18.

[11] Electoral Boundaries Act (Prince Edward Island), Chapter E-2.1, at section 17(2); Nova Scotia Electoral Boundaries Commission, “Terms of Reference,” in Final Report: Balancing Effective Representation with Voter Parity, April 2019, at page 5; Electoral Boundaries and Representation Act (New Brunswick), RSNB 2012, c. 106, at section 10; Loi électorale (Québec), chapitre E-3.3, à la section 14;

[12] Electoral Boundaries Act (Newfoundland and Labrador), RSNL 1990, Chapter E-4, at section 13(3); The Electoral Divisions Act (Manitoba), C.C.S.M., c.E40, at section 9; The Constituency Boundaries Act, 1993, Statutes of Saskatchewan, Chapter C-27.1, at section 13(2); Electoral Boundaries Commission Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter E-3, at section 15(1); Electoral Boundaries Commission Act (British Columbia), RSBC, Chapter 107, at section 9(1).

[13] Eric Grenier, “Liberal Winners in New Toronto and Peel Map,” The Writ, 14 August 2023; Eric Grenier, “Liberals Lose Out in New Map for Ontario’s Regions,” The Writ, 29 August 2023.

[14] Philip Kaye, “Redistribution of Electoral Districts in Ontario,” Ontario Legislative Library, September 1996, at page 7.

[15] Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Select Committee on Electoral Reform, Report on Electoral Reform, 38th Parliament, 2nd Session, 54 Elizabeth II, at page 41.

[16] Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Memorandum from the Research and Information Services to the Select Committee on Elections, 20 January 2009, at page 23.

[17] Elections Ontario, Ready for Change: 2015-2016 Annual Report, at page 23.

[18] Elections Ontario, Ready for Change: 2015-2016 Annual Report, at page 24.

[19] Elections Ontario, Advancing Change: 2016-2017 Annual Report, at page 32.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Elections Ontario, Implementing Change: 2017-2018 Annual Report, at page 34.

[22] Elections Ontario, Modernizing Ontario’s Electoral Process: Report on Ontario’s 42nd General Election – June 7, 2018, at page 11.

As usual, James, you have provided a comprehensive and indispensable analysis of this significant democratic problem. I only hope something comes of it. Ignorance is not bliss.

LikeLiked by 1 person