The Canadian Study of Parliament Group (CSPG) held a seminar on “Dissecting Redistribution” on Friday, 14 April 2023, which consisted of three panels on the process of the decennial redistribution, the perspectives of four current members of various Federal Electoral Boundaries Commissions (FEBC), and another on academic perspectives. Despite what the poster says, the second panel featured Kenneth Carty (Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of British Columbia and a member of the Commission for British Columbia), Kelly Saunders (Professor at the Department of Political Science at Brandon University and member of the Commission for Manitoba), Karen Bird (Professor of Political Science at McMaster University and member of the Commission for Ontario), and Louis Massicotte (Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Universite Laval and a member of the Commission for Quebec). The third and final panel consisted of Michael Pal (Professor of Law at the University of Ottawa), Glenn Graham (Professor of Political Studies at Cape Breton University), Remi Leger (Professor of Political Science at Simon Fraser University), and Tamara Small (Professor of Political Science at the University of Guelph).

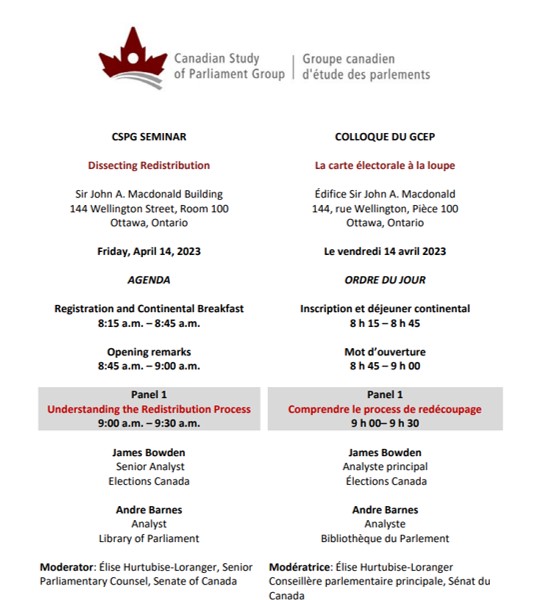

I presented on the first panel alongside Andre Barnes of the Library of Parliament. I wish that we had had more time to present on the complex minutia of this process, so vital and yet so poorly understood even by MPs themselves and politicos because it happens only once every ten years. My superiors at Elections Canada gave similar but more comprehensive briefings to the caucuses of the four largest parties in 2022, at their requests, and needed close to an hour to delve into the details. But perhaps I can do so here later.

Panel I: Understanding the Redistribution Process

The decennial electoral redistribution in Canada flows from two sources, the Representation Formula contained with section 51(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867 (which Parliament can amend at will under the Section 44 Amending Procedure) and the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act. The Representation Formula determines the number of MPs, and thus seats, per province through a series of rules that layer several exceptions onto the basic principle of representation by population. Parliament overhauled the Representation Formula in December 2011 so that it could apply to the decennial redistribution in the 2010s, and Parliament made a minor amendment to it again in June 2022.

Under major amendments that Parliament applied to EBRA in December 2011, the overall process lasts about two years. The current redistribution began in October 2021, when the Chief Electoral Officer calculates the number of MPs per province, and will conclude in September 2023, when the Governor-in-Council promulgates the Representation Orders under EBRA, the formal legal instrument which implements the new electoral districts that the ten independent electoral boundaries commissions created.

Panel II: Perspectives from Members of the Commissions

A: Kelly Saunders (Manitoba)

Kelly Saunders started out by going over the number of MPs for Manitoba and its resulting electoral quota under EBRA.

She showed a chart of the populations of all the electoral districts of the province. In total, 13 of 14 districts saw increases in population, the exception being the sprawling northern riding of Churchill – Keewatinook Aski, the fourth largest electoral district by surface area in all of Canada and takes up three-quarters of Manitoba. However, growth remained uneven and concentrated in and around Winnipeg; for instance, Provencher’s population increased by 23.47%, compared to an increase of only 4.51% for Winnipeg South Centre. The Commission looked at rural vs urban ridings and saw no clear patterns in the shifts in population.

Saunders spoke of the requirements under EBRA, which, in her view, “contradict each other.” She added that “there’s no priority ordering in the legislation on how they should be applied.” But she then described voter parity as the “first principle,” and it does, in fact, appear first in section 15 of EBRA.

Manitoba’s Commission chose to interpret the rules under EBRA based on the following guiding principles, in this order:

- Population equality, with the ideal that each electoral district would come in at only plus or minus 5% of the electoral quota, a goal to which all Commissions for Manitoba since the 1990s have hewed;

- Population growth projections (even though EBRA no longer makes provision for this);

- Communities of interest and identity in terms of municipalities, indigenous communities, bilingual areas of the province; and,

- Geography with respect to maintaining reasonable geographic sizes.

The Proposal increased the population of the riding of Churchill by 8,000 and then adjusted the other ridings accordingly. The Commission started north, with Churchill – Keewatinook Aski, and worked its way down toward Winnipeg and sought to cut the variance from the electoral quota of Churchill from -15 to -8% adding 8 First Nations communities to it.

Manitoba held four public hearings and heard opposition to hybrid ridings. They received 709 submissions and presentations, and 11 of 14 MPs participated in the process. She was surprised that citizens themselves didn’t care so much about population equality. (This became a common theme, with Michael Pal making similar remarks).

Even seven Conservative MPs signed a joint letter advocating on behalf of New Democratic MP Niki Ashton, who represents the big riding of Churchill – Keewatinook Aski. All these MPs, of various parties, agreed on effective representation over strict adherence to population equality. MPs spoke eloquently on the challenges of representing an enormous geographic area. First Nations are often under-counted in the decennial census anyway, which probably makes Churchill’s true variance from the electoral quota lower than the official figures suggest.

The Commission struggled to define what effective representation means and sought to balance it with voter equality. Saunders acknowledge that she “is not quite sure if they got it right in Manitoba.” She emphasized that the Commission listened to MPs’ objections and “took them into account in the final decision.”

Only one individual recommended invoking the “exceptional circumstances clause” (presumably not her), but the Commission ultimately rejected that option for Churchill – Keewatinook Aski.

B: Kenneth Carty (British Columbia)

Carty noted that his Commission had to decide where to add the one additional MP that the Representation Formula granted British Columbia in this round of redistribution. British Columbia’s population remains fundamentally bound in by mountains and the sea and thus highly concentrated in some areas and vast wilderness in between. As Carty says: “Single-member districts are about geography.” The Commission therefore decided to divide British Columbia into four regions: Vancouver Island, the Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley (which includes Vancouver), the Southern Interior, and the North. The Commission then examined the disparities of population within each region, devised regional electoral quotas separate from the official provincial quota, and then awarded the one extra seat to the Southern Interior because it showed the greatest disparities in population. The Lower Mainland contains 62% of the population compared to only 7% in the North. Vancouver Island’s population remained steady, but the Southern Interior had developed over the last decade the greatest average variance of 10.4% from the electoral quota, so the Commission awarded this region the extra seat. This reduced the disparity in population between electoral districts across the four regions. The Commission accepted early on different variations in the four regions, ranging from -7.2% to +5%.

BC’s Commission held 27 public hearings, heard 211 formal presentations and fielded more than 1,000 written submissions. The judge and chair was very keen on holding these hearings and would have held more! The Lower Mainland, which the border with the United States and the Fraser River and the Pacific provide hard barriers, proved the most contentious. The Commission’s Proposal adhered to the Fraser River in drawing up boundaries. But the Commission nevertheless significantly altered the Fraser Valley Region in its Report. The Commission made major changes in making some ridings cross the Fraser, but all splitting up fewer municipalities and better recognising communities of interest in the Southern Interior. (Incidentally, the Report has also provoked controversy at PROC amongst MPs from Vancouver and Richmond for this reason).

The Commission sought to minimize disparity in population within regions and adopted four regional quotas instead of using the provincial quota as the main baseline. Only 3 of the 43 ridings remained intact as a result of these extensive changes. Most of these ridings vary from the provincial electoral quota (23 of 43) within -2 to +2%. Only one electoral district went beyond -10% in the end.

Carty boasts that this Report has given British Columbia is “most ‘equal’ redistribution since the creation of independent commissions.” He showed a chart illustrating variations in 1966, 1976, 1987, 1996, 2002, 2012, and 2022; the variations from the electoral quota in 2022 are indeed the smallest.

C: Karen Bird (Ontario)

Bird emphasized that Ontario’s Report is still before PROC and thus not yet done.

Ontario gained one MP, bringing the total to 122, which is 56% more districts than those of the next largest province, Quebec. Yet Ontario’s Commission still gets the same amount of time as all the others. Ontario certainly could not undertake a second round of public hearings, even though the Report contained substantive changes relative to the Proposal.

Ontario faces numerous challenges, especially disparities in the rate of population growth across various regions. The North and Toronto grew slowly and thus each lost one seat.

The challenges in the North include effective representation of indigenous peoples and Franco-Ontarians. Ontario faces another unusual situation in that the provincial legislature decided in the 1990s (through the hilariously named Fewer Politicians Act) to tie all the federal electoral districts, except those in the North, to its own provincial electoral districts in Queen’s Park. Furthermore, Queen’s Park later enacted legislation tying the City of Toronto’s wards to the provincial, and thus federal, ridings as well. This means that the City of Toronto will lose a ward under the province of Ontario’s current legislation. The province has, however, established a Far North Electoral Boundaries Commission which gives the North a few extra seats. Under legislation from 2005, the North gives 11 provincial electoral districts, but with this latest redistribution, the North only has 9 federal districts. The divergence continues to grow with each decennial redistribution.

Ontario’s Commission started by organising the 121 existing districts into 15 regions. The North grew by only 2.8%, compared to 11% in the rest of the province. The previous Commission in 2012 maintained 10 districts in the North by allowing large variances from the electoral quota. Adhering strictly to voter parity would have necessitated taking two seats away from the North (leaving it with only 8 in total), but the Commission in 2022 decided to take away only one, leaving it with 9. In its Proposal, the Commission sought to establish 8 districts within -15% plus one large riding with a majority-indigenous population that would have been 69% below the quota. The Commission deliberated proposed a majority-indigenous riding.

In addition, Toronto grew by only 6.9% compared to 11.7% in the rest of the province. So Toronto also had to lose one seat, from 25 to 24. The Proposal removed that seat from Scarborough, which, as the Commission learned, possesses a powerful sense of community identity.

Three of the 15 regions stood out as significantly under-represented: the Eastern GTA, Brampton-Caledon-Dufferin, and Halton-Guelph-Wellington. The Proposal gave one seat to Halton-Guelph-Wellington, another to Brampton-Caledon-Dufferin, and then, in effect, one-half of a seat each to Central Ontario and the Eastern GTA, where one seat straddles the two regions. The Commission ended up changing the vast majority of the boundaries of electoral districts in its Report.

Ontario’s Commission received an unprecedented level of public input in 2022, a massive 75% increase over what its predecessor Commission received in 2012. In 2022, Ontario’s Commission held 23 public hearings, heard 462 representations, and received 1,899 written responses. The major objections related to taking away one seat from the North, and one from Toronto, as well as splitting up municipalities and not respecting communities of interest and identity. The Commission accepted that the proposal huge northern district was simply too large and thus unmanageable. Indigenous communities themselves opposed this proposal for a majority-indigenous district because that proposed district did not contain the various municipal hubs in northern Ontario to which their communities are connected. Franco-Ontarians also objected to being split into different ridings in the North.

Many objections accused the Census of being inaccurate and having under-counted the population of Toronto during the pandemic. Objections in Toronto also noted that losing a federal seat means losing a provincial seat and a municipal ward. Those who objected to the Proposal cared more about communities of interest than voter parity.

The Commission went back to the drawing board and considered letting the North keep 10 seats. But if the North kept 10 seats, the average seat in that region would come in at -15% of the quota. However, the Commission extensively re-drew the boundaries in the North, keeping one northwestern and one northeastern district, which respects Treaty 3 First Nations. The North now contains three “extraordinary circumstances” districts, and the others fall within -15% of the quota. These ridings in the Report better represent Franco-Ontarian communities as well.

The Commission also reorganised Toronto, redistributing the loss of a seat in Scarborough with the areas closer to downtown Toronto. This actually allowed the Commission to make fewer changes to the boundaries in Toronto overall. But Toronto still lost one seat.

The Commission also re-jigged the districts in Halton-Guelph-Wellington to avoid splitting the city of Burlington across 4 and the municipality of Oakville across 3 districts. The Report now better respects these municipal boundaries. The Commission has now split Oakville into 2 districts, but this cascaded across the region and necessitated other changes to four other ridings.

Bird acknowledged that the Report has made significant changes relative to the Proposal. She would like that Ontario be given more time to present the changes in the Report.

In 2022, only 20 of 122 districts push beyond plus or minus 10% of the quota. In contrast, 41 of 121 went beyond this variation in 2012.

D: Louis Massicotte (Quebec)

Massicotte noted that the Commission for Quebec encountered the following things throughout its work:

- Resistance to change

- Positive effects of the public hearings

- Public confusion between Elections Canada and the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commissions.

Quebeckers really did not like change. And it is worth noting that Quebec’s Commission kept 24 of 78 ridings intact relative to the previous redistribution – by far the largest percentage across the 10 provinces. So the Commission really tried to respond to this particularity in Quebec.

The Commissions should ensure that the populations of the electoral districts do not vary too much from the electoral quota. Massicotte showed a chart on the measure of electoral inequality of the ten provinces. Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island came in low, which means a stricter adherence to the electoral quota and stronger voter parity overall. In contrast, Newfoundland and Labrador shows the highest distortions, followed by Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.

Quebec faced the unusual distinction of the uncertainty of how many electoral districts the province had, going from 77 to 78 in the middle of the process. The Commission suspended its work for 2 weeks while Parliament was debating the two bills to amend the Representation Formula. The Commission continued to work on a hypothetical 78 seats after the government introduced Bill C-14, which seemed sure to pass. Quebec`s Commissioners declined PROC`s invitation to appear as witnesses during the study of Bill C-14. The Commissioners found the amendment and restoration of 78 seats “a great relief,” because redistricting is much easier with the same number of seats than with losing one.

The Commission also decided to add indigenous toponyms into the names of 11 ridings, to acknowledge each of the 11 indigenous groups. He described this decision as “an initiative of the Commission and not a reaction to indigenous claims.” This “initiative was less highlighted in the media than it deserved,” in Massicotte’s estimation. The Commission also wanted to put indigenous names first in the names of the ridings. One chief asked the Commission to create a majority-indigenous district in the North, which would have meant creating two ridings with populations greater than 25% below the quota. The Commission rejected that suggestion.

Panel III: Academic Perspectives on Redistribution

A: Michael Pal

Pal spoke of how Parliament has changed the Representation Formula since Courtney’s book Commissioned Ridings came out in 2001, but not the criteria and rules under EBRA. He sees a strong divergence in how the Commissions interpret the legal criteria to the point where “they’re engaging in different enterprises.” Pal continued: “This looks problematic because a similarly situated citizen in one province is treated differently from that of another province.” He believes that Parliament should amend the rules under section 15 of EBRA to reduce these disparities and impose a stricter common framework that the ten Commissions must follow.

For instance, EBRA does not define “community of interest.” Parliament debated amendments in the 1990s but never enacted them. Some Commissions have declared that only rural and urban communities of interest exist, while other Commissions consider ethnic, linguistic, and indigenous groups. Given that EBRA contains no definition, each Commission can create its own interpretation of what “community of interest” means. Pal believes that Parliament should amend EBRA to better define what “community of interest” means. This might bring up difficult controversies in this country over language and ethnicity, etc.

Pal also pointed out that all four of the Commissions represented here today on the previous panel (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec) chose to adhere to variances much stricter than the plus or minus 25% permitted under EBRA. He spoke of lowering the acceptable variances to plus or minus 10%, coupled with precise exemptions for northern regions of various provinces that would therefore use different quotas from the rest of the province.

Pal noted that the Lortie Commission on Electoral Reform observed in the early 1990s that electoral boundaries commissions had not up to that point taken indigenous communities into account. Commissions have taken upon themselves to do better, but EBRA has not been updated to reflect these concerns. He believes that “more statutory guidance is helpful,” based on his experience as a member of the Far North Electoral Boundaries Commission of the province of Ontario in 2017.

The constitutional case law compounds all this. The courts have broadly ruled in favour of “effective representation” rather than “one person, one vote.” Representation by population forms the baseline, but is not the only factor.

Pal spoke of Canada’s anomalous position compared to other OECD countries. Most jurisdictions impose far stricter variances from the electoral quota compared to what Canada allows under EBRA. While he doesn’t normally look to the US for guidance on this issue, he points out that some states in the US list criteria of what commissions must consider and in what order they must consider them. He would like that Parliament amend EBRA to do something similar.

Pal also wonders whether Commissions are unduly fettering their own discretion by imposing limits on themselves that EBRA itself does not spell out, which, in turn, means that we could see litigation on this issue after this round of redistribution.

While Parliament amended the Representation Formula in 2011 and 2022, it has not changed the rules under section 15 of EBRA to match. Overall, the Commissions have improved the electoral maps over the last 20 years, but significant disparities and contradictions remain – which will entail litigation in constitutional and administrative law.

B: Glenn Graham

Graham has decided to focus on his experiences on a provincial redistribution in Nova Scotia in 2018-2019 rather than on the current federal decennial redistribution in the 2020s. He’s also looking at New Brunswick and Manitoba.

He described the approach of historical institutionalism in studying electoral redistribution. He spoke of path dependency and punctuated equilibrium. He spoke in the depressingly common political science gobbledegook of “exogenous shocks” and “critical junctures” and “policy windows.” He then reviewed the theory of incremental and gradual institutional change.

In 1957, Manitoba became the first jurisdiction in Canada to adopt independent electoral boundaries commissions, and other provinces and Canada at the federal level followed suit over the next decade.

He sees the early 1990s as leading to a confluence of factors which created a policy window for institutional entrepreneurs. In particular, 1992 became a critical juncture in Nova Scotia when commissions started recognised Acadians and Black Nova Scotians as worthy of representation as communities unto themselves. In 2019, Nova Scotia restored protected ridings for Acadians and blacks, which shows institutional embeddedness going back to 1992.

C: Remi Leger

He spoke of “effective representation.”

In 2012, Nova Scotia abolished its four “protected constituencies”, established in 1992 and implemented in 2002. Three recognised Acadians, and one recognised black Nova Scotians in the Halifax area. The Commission’s report was rejected as null and void because it did not respect its mandate.

Five provinces – BC, ON, QC, NS, and NL – allow variances beyond the default in exceptional circumstances, without qualification and without limit, in their provincial electoral redistributions.

In his view, “effective representation” is very Canadian: flexible, and adaptable, not strictly defined.

D: Tamara Small

Small spoke primarily of public participation in the redistribution process and is building on Courtney’s work from Commissioned Ridings in 2004 by looking at the last two rounds in 2012 and 2022.

In 2012, some Commissions held teleconferences, but 2022 marked the first time that Commissions held properly virtual public hearings. Commissions in MB, PEI, and NB cancelled some public hearings due to lack of interest. But under their criteria, NL would have to have cancelled many of its hearings as well. Commissions do not always publish the exact numbers of participants per hearing. But the numbers have never been large. Compiling the data is difficult because some Commissions say nothing, and in 2022, some Commissions did not distinguish between participants in normal vs virtual public hearings.

In 2001, Courtney said that 828 people in the 1980s and 948 in the 1990s participated in public hearings. Most of these were written submissions rather than public representations. The last two in 2012 and 2022 have seen significant greater public participation, though the number of participants vary within provinces, depending on the nature of boundaries changes.

Ontario has the largest number of participants. But Nova Scotia had the fifth-largest number of representations and the second-largest number of written submissions at 1,000 – despite being 7th in population. NS saw a huge increase in participation relative to 2012.

In 2012, Saskatchewan made significant changes, which brought 3,000 written comments and 200 representations. But in 2022, Saskatchewan saw far fewer.

Participation depends upon the nature of the changes that Commissions propose.

Mayors, councillors, MPs, MLAs, etc. made up the bulk of the interveners, according to Courtney’s research.

Alberta in 2022 note that 12 sitting MPs made representations. In Manitoba, 11 out of 14 MPs participated. Only one in four participants in NL came from the general public. In NB, 4 of 7 MPs participated, but 61% of comments came from the general public; the next biggest category was mayors.

Technology has resulted in increases in participation; it’s easy to send a written submission by email.

Courtney mentions that MPs can participate twice, both in public hearings and at PROC, which he sees as a real issue. If we want to de-politicise this process, then MPs probably shouldn’t get this chance to participate twice.

Questions and Answers on Panel III

Charles Feldman of CSPG asked about the incentive that MPs have in not losing their jobs. Remi Leger mentioned that some Commissions made significant changes between their Proposals and Reports, even though the public cannot comment on those latter changes.

Professor Carty followed up on Michael Pal’s comments on the criteria in EBRA. He touted the “most equal map in British Columbia’s history.” Yet British Columbia’s provincial commission has just produced the most unequal provincial redistribution of all time! The Commissions operate in unpredictability. There is no consensus, “even amongst those in the business of commissioning.” “It’s an open question and we need some kind of statutory rethink.”

One member of the audience asked if any consideration has been given to disparity between provinces. Michael Pal stressed that a federation like Canada ought to establish different commissions for each province and that he does not believe that the Commissions should make identical decisions. However, it is strange that Commissions can, in effect, pick their own rules, and often in direct opposition to one another– even though they all derive their authority from the same statute. We must bear in mind that the Representation Formula, not EBRA, determines how many MPs each province gets. He spoke favourably of the 6th Representation Formula from 2011, which tried to correct the under-representation of BC, AB, and ON by giving them 30 new seats in one fell swoop. The Constitution guarantees the less populous provinces fixed representation, so we can only correct the under-representation of the three fastest-growing provinces by giving them additional seats. There are downsides to having a larger House of Commons, which need to be weighed against concerns of representation.

Erin Crandall (the moderator of the third panel) asked about communities of interests and whether MPs would be willing to debate this contentious topic of how they should define what this means in any amendments to EBRA. Michael Pal mentioned that the House of Commons undertook a very divisive debate on this subject in the 1990s, and any debate today would probably prove even more contentious. The crux divides along whether “community of interest” refers primarily to geographic considerations like not splitting up municipalities or recognised natural geographic features like rivers and mountains, versus whether this term should refer to properly demographic considerations like ethnicity and indigenous communities.

Similar Posts:

- Readjusting Electoral Districts in Federations: Malapportionment vs Gerrymandering (August 2022)

- CSPG Conference: Paul Dewar Dodged My Question on Section 52 and Over-Representing Quebec (October 2011)

- James W.J. Bowden, “Favouring Quebec in Parliament Is Unconstitutional,” National Post, 17 October 2011

- My Column in the National Post on the New Democrats’ Unconstitutional Private Members’ Bill to Give Quebec a Fixed Proportion of Seats (October 2011)

- The New Democrats’ Anti-Constitutional Stance on Electoral Redistribution (September 2011)