Britons went to the polls on 4 July 2024 and ended up giving Labour a massive majority of 411 out of 650 MPs. By the next morning, outgoing Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had already tendered his resignation to His Majesty King Charles III, and the King appointed Sir Keir Starmer, leader of the Labour Party, as the next Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Prime Minister Starmer then announced that the King had approved his ministerial appointments.[1] The website of Number 10 Downing Street also already includes Sir Keir’s biography and lists his press releases.[2] The British accomplish in one day what Canada takes three weeks to do! Furthermore, the House of Commons met on 9 July, with Sir Keir and Sunak having switched sides and despatch boxes. The King will open the first session of the next parliament on 17 July, a mere two weeks after the day of the election.[3] The British waste no time. In contrast, a new parliament in Canada would not meet until around eight weeks after the new prime minister assumes office, for a total of some eleven weeks after the election.

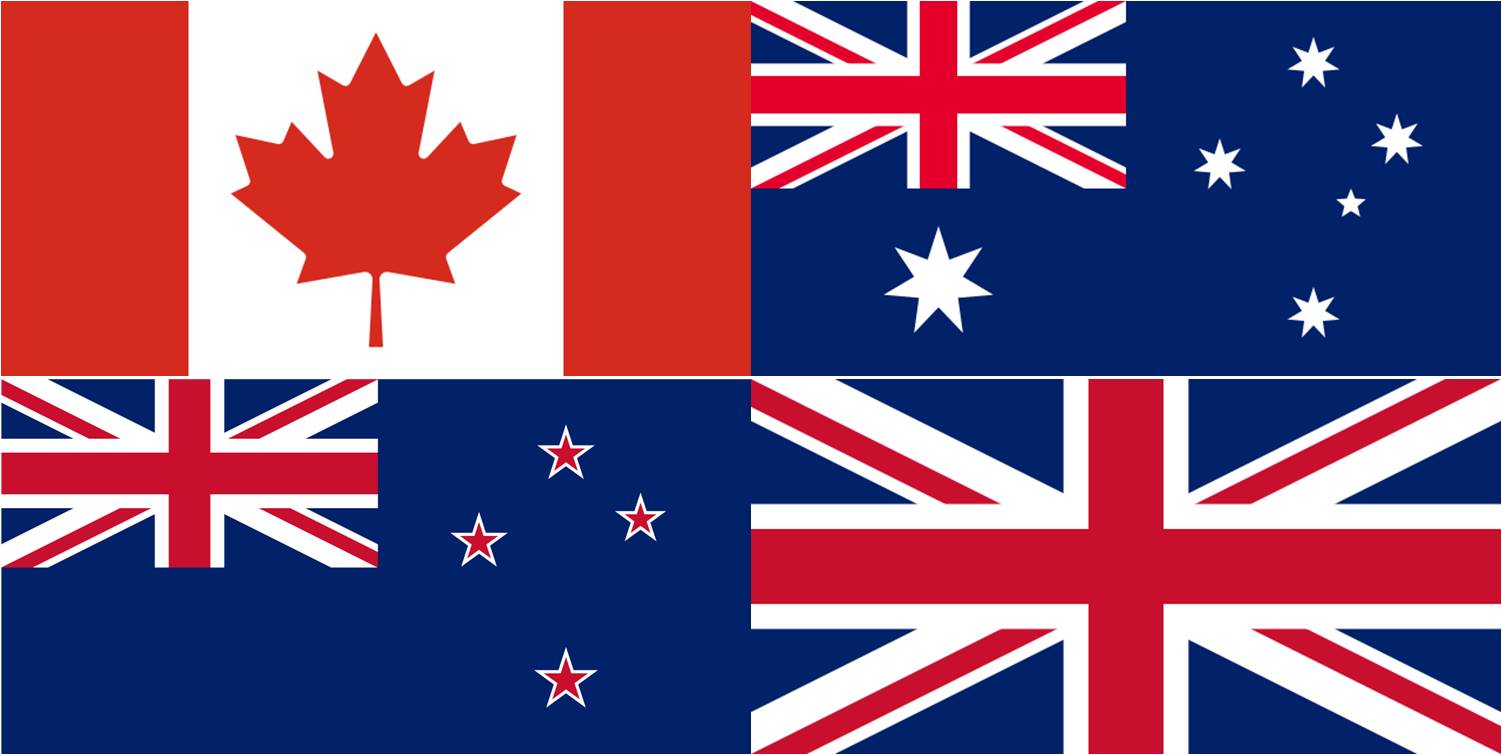

Yet despite these obvious differences, scholars of Westminster parliamentarism routinely emphasize and take comfort in the shared heritage of the Commonwealth Realms and too often gloss over – or are even perhaps ignorant of – the interesting differences that have emerged over the decades, some trivial and some major. In this piece, I have highlighted another interesting difference, this time not merely between Canada and the United Kingdom, but across the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. These four Realms which have practised self-government the longest cannot agree amongst themselves and have diverged into at least three (or four, counting the widespread view on the British method) separate standards on something as simple how to count the number of ministries which have governed them since x date.

The Constitutional Conventions of Appointing Prime Ministers in Canada

In Canada, the tenure of the Prime Minister determines the tenure of the ministry as a whole; therefore, the Prime Minister’s resignation or death automatically forces the resignation of the entire ministry at once.[4] The Oxford Dictionary defines a ministry as “a period of government under one prime minister,” and the Privy Council Office has rigorously hewed to that definition in its Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation.[5] A single ministry can therefore span multiple parliaments, and a single parliament could include multiple ministries.[6] For instance, Stephen Harper’s 28th Ministry remained in office continuously from 6 February 2006 to 4 November 2015 and spanned the 39th, 40th, and 41st Parliaments elected in 2006, 2008, and 2011, respectively.[7] Alternatively, a single parliament might overlap with multiple ministries. The 2nd Parliament elected from July to October 1872, for instance, included two ministries because Sir John A. Macdonald resigned over the Pacific Scandal and Governor General Lord Dufferin appointed Alexander Mackenzie as the next Prime Minister in November 1873.[8] More recently, the 37th Parliament elected in 2000 saw an intra-party transition of power between the 26th and 27th Ministries of Chretien and Martin in December 2003.[9]

However, one precedent stands out as a notable exception in Canada: the Tenth Ministry of Sir Robert Borden.[10] Even though Borden remained in office continuously as Prime Minister from 10 October 1911 to 10 July 1920, the Guide records that Borden headed two distinct ministries, the Ninth from his appointment on 10 October 1911 to 12 October 1917, and the Tenth from 12 October 1917 to his resignation on 10 July 1920. PCO probably chose to break up Borden’s premiership into two ministries because the Conservatives ran on a joint slate with most English-speaking Liberals in the wartime election of 1917 and governed in a coalition with them thereafter. Even PCO seems unconvinced by its own decision to list them as separate ministries instead of as one ministry which underwent a big cabinet shuffle after the election in 1917: “The Tenth Ministry was in effect a re-organization of the Ninth with the addition of a number of Liberal and Labour Ministers. In addition to Borden, it was composed of 15 Conservatives, 9 Liberals, and 1 Labour.” In all other instances (Macdonald, King, and Trudeau), a Prime Minister only led two or more ministries if he had resigned and the Governor General re-appointed him again later after some months or years in opposition.

In Canada, the transfer of power between ministries usually takes place two to three weeks after a general election or leadership convention in the following manner:

- The incumbent Prime Minister informs the Governor General that he intends to resign based on the results of the general or leadership election and becomes the “outgoing” Prime Minister;

- The leader of the party which won the largest number of seats, or the new leader of the incumbent party (whether an outright majority or only a plurality) becomes the “incoming” Prime Minister as the only plausible candidate;

- Within a few days, the Governor General formally recognizes the incoming Prime Minister as the “Prime Minister-designate” and asks him to prepare to form a government;

- The outgoing Prime Minister and Prime minister-designate agree to the exact timeline for the transition between their ministries;

- Finally, some two to three weeks later, the Governor General formally accepts the resignation of the outgoing Prime Minister and swears in the Prime Minister-designate as Prime Minister, along with the rest of the cabinet ministers in his ministry.[11]

The provinces follow the same method.[12] The most recent transfer of power between ministries in Ottawa happened in October and November 2015. On 19 October 2015, Canadians awarded the Liberals a parliamentary majority in the 42nd Parliament; the clear results of this general election made Conservative leader Stephen Harper the outgoing prime minister and Liberal leader Justin Trudeau the incoming prime minister that same night. The following day, on 20 October 2015, Stephen Harper informed Governor General David Johnston that he intended to resign as Prime Minister of Canada; Johnston summoned Justin Trudeau later that day and recognised him as the Prime Minister-designate. Finally, on 4 November 2015, the Governor General accepted the resignation of Stephen Harper, and thus that of the 28th Ministry as a whole, and subsequently swore in Justin Trudeau as Prime Minister along with the rest of the cabinet for the 29th Ministry.[13]

The previous transfer of power took place in January and February 2006. On 23 January 2006, Stephen Harper’s Conservatives won only a plurality of seats. Prime Minister Paul Martin could therefore have decided to remain in office, try to win the support of the New Democrats and Bloc quebecois, and test the confidence of the new House of Commons; instead, he took to the podium to concede defeat and announced that he would resign as Prime Minister of Canada and as leader of the Liberal Party.[14] Consequently, Stephen Harper became the incoming prime minister and delivered a victory speech that same night. Governor General Michaelle Jean formally recognised Harper as the Prime Minister-designate three days later on 26 January 2006, and she formally accepted the resignation of Martin and the 27th Ministry and appointed Stephen Harper as Prime Minister and head of the 28th Ministry on 6 February 2006.[15] In contrast, this concept of “Prime Minister-designate” simply does not exist in the United Kingdom because the King appoints a new prime minister with minimal delay, as we all just saw a few days ago.

This transition of two to three weeks allows the Governor General to appoint the new Prime Minister and the rest of the new ministry at the same time in one fell swoop. But prior to 1920, Canada followed the British method where the King appoints a new Prime Minister the day after the general election or a leadership election but not the rest of the ministry at the same time.[16] In the United Kingdom, the incumbent Prime Minister tenders his or her resignation to the King as soon as the results make clear that his or her party has lost a general election (usually the following day, though 2010 stands out as an exception here because of the hung parliament), which, in turn, allows the King to commission the leader of the party which won the most seats as the next Prime Minister right away.[17] Other ministers, however, might stay on for a few more days in a short transition, and the King appoints new ministers on the new Prime Minister’s advice.

Only in parliamentary jurisdictions which use confirmation voting (such as in the devolved assemblies in Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Scotland, and Wales; in some parliamentary republics like Germany and Israel; or in constitutional monarchies like Spain) does the Crown or President possess no discretion whatsoever in appointing a Prime Minister but instead must appoint whomever the elected assembly has nominated.[18] Sweden has taken confirmation voting a step farther and cut the King out of the process altogether; instead, the speaker of the lower house appoints whomever his colleagues nominate.[19] And in Northern Ireland, the confirmation vote itself doubles as the appointment, presumably because the Irish nationalists demanded during the negotiations over the Belfast Accords in 1998 that the Crown play no role whatsoever in the Northern Irish Assembly and Executive.[20] This arrangement undermines the Crown and British Unionists and advances the Irish nationalists’ goal of incorporating Northern Ireland into the Republic of Ireland. The prime minister in these jurisdictions therefore remains in office during the election and after the election until meeting the new elected assembly, which then either votes that the incumbent be re-appointed or nominates a new prime minister.[21]

Different Practices in the Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom

Logically, this same principle should apply in all the Commonwealth Realms, unless they have adopted confirmation voting (as in the devolved territorial assemblies of Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and the devolved assemblies of Scotland and Wales). But Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom now all seem to have diverged along their own paths. The British Cabinet Manual contains the same definition of ministry as the Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation and other Canadian sources like the Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada.[22] While the British therefore officially use the Canadian definition, the Cabinet Office has not done its due diligence in cataloguing British ministries since the Act of Union, 1707 into an official handbook equivalent to our Privy Council Office’s Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation. The absence of an official and authoritative book opens up ambiguity that unofficial outlets can exploit and use to push their own erroneous definitions and categorisations, like the invisible college of Wikipedia editors has done.

In the Antipodes, the New Zealanders likewise tie the ministry to the prime minister[23] while also referring to continuous stretches where one party remains in power under two or more prime ministers as the “nth party government.”[24] The Kiwis have layered on this addition rather than replacing the original definition of ministry. If Canada used this method, the period from 1980 to 1984, which saw two consecutive Liberal ministries (the 22nd and the 23rd) headed by Pierre Trudeau and John Turner, respectively, would be called “the 7th Liberal Government” because those years marked the seventh stint of Liberal Prime Ministers since Confederation. In contrast, the Australians reject the Oxford definition outright and tie a ministry to both the prime minister and the parliament such that no ministry can span multiple parliaments, but one parliament could still contain multiple ministries.[25] Under the Australian model, Stephen Harper led three consecutive ministries in three consecutive parliaments.

The British Cabinet Manual indicates that “Prime Ministers hold office unless and until they resign” but that “Rarely, a Prime Minister may resign and then be asked to form a new administration.” For example, “Ramsey MacDonald resigned as Prime Minister of a Labour government and was reappointed as Prime Minister of a National Government in 1931. Winston Churchill was also asked to form a new Conservative administration following the break-up of the wartime coalition government in 1945.” Those two British precedents both correspond closely to the lone Canadian example involving Sir Robert Borden’s uninterrupted 9th and 10th Ministries, the latter of which included a new coalition government of Conservatives, Liberals, and Labour.[26]

Despite the fact that the British Cabinet Manual confirms that the British practice corresponds precisely to that articulated more clearly in Canada, Wikipedia has decreed that all British Prime Ministers who served in office for an uninterrupted term nevertheless laboured under separate ministries. This nonsense directly contradicts the facts. Margaret Thatcher served continuously from 4 May 1979 to 28 November 1990 under one ministry, not with the “First Thatcher Ministry,” “Second Thatcher Ministry”, and “Third Thatcher Ministry” on which Wikipedia insists. The same goes for Tony Blair, who headed but one ministry and not “Blair I,” “Blair II,” and “Blair III.” Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II invited Margaret Thatcher to become Prime Minister once in total, in 1979, not once after each election in which she led the Conservatives to majorities in 1979, 1983, and 1987. Similarly, Elizabeth II only invited Tony Blair to form a government once, in May 1997, and not again in 2001 and 2005. However, one could make a reasonable case for a Cameron-Clegg ministry from 2010 to 2015 and a subsequent Cameron ministry from 2015 to 2016, in analogy to the Canadian precedent with Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative ministry and subsequent Conservative-Liberal coalition ministry.

Margaret Thatcher confirms here in her own words that she headed one ministry from 1979 to 1990, not three ministries with one after each election, because Queen Elizabeth II only asked her to form a government once, on 4 May 1979. Thatcher recounts in her prime ministerial memoir that “We knew that we had won in the early hours of Friday 4 May, but it was not until the afternoon that we gained the clear majority of seats we needed – 44 as it eventually turned out.” Thatcher adds that the Palace called her around 2:45 p.m. and that the Queen asked her to form a government that same afternoon. Here Thatcher also refutes the narrative in British Wikipedia and confirms that the British conform to the Canadian practice:

“The Audience at which once receives the Queen’s authority to form a government comes to most prime ministers only once in a lifetime. The authority is unbroken when a sitting prime minister wins an election, and so it never had to be renewed throughout the years I was in office.”[27]

Tony Blair also confirms in his autobiography that the Queen made him Prime Minister the day after he led New Labour to a crushing majority the general election in May 1997: “On 2 May 1997, I walked into Downing Street as prime minister for the first time. […] The election night of 1 May had passed in a riot of celebration, exhilaration and expectation.” [28]

In the entry for “Ministry,” the erroneous editors of Wikipedia insist that, “In the United Kingdom and Australia, a new ministry begins after each election, regardless of whether the prime minister is re-elected, and whether there may have been a minor rearrangement of the ministry.” It is telling that they could only offer a legitimate endnote to support that claim with respect to Australia, because it only applies to Australia and does not accurately describe the constitutional position in the United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, “ministry” as the “government of the day as a whole”, “led by particular Prime Ministers,” and tied to the tenure of the Prime Minister fell out of use by the early 20th century.[29]

Australia takes a different view and ties the ministry to both the prime minister and the parliament, although the Governor General still commissions the prime minister before opening the first session of the new parliament because Australia does not do confirmation voting.[30] For instance, John Howard served as Prime Minister of Australia continuously from 11 March 1996 to 3 December 2007. Under the Canadian model, he clearly led only one ministry because he served one continuous stint in office across four parliaments. However, the Australians insist that he headed four distinct ministries during that time corresponding roughly to the election of each of the four consecutive parliaments in which he led the Liberal-National coalition to four majorities. The Australians maintain that the 54th Ministry is the First Howard Ministry, that the 55th Ministry is the Second Howard Ministry, that the 56th Ministry is the Third Howard Ministry, and that the 57th Ministry is the Fourth Howard Ministry. Kevin Rudd would even under the Canadian method have led two ministries because he served in two non-consecutive stints as Prime Minister, first as head of the 58th Ministry from 3 December 2017 to 24 June 2010, and again as head of the 61st Ministry from 27 June 2013 to 18 September 2013. The Australians of course also count these as the First and Second Rudd Ministries. Consequently, the Commonwealth of Australia has had 31 Prime Ministers but 67 ministries between 1901 and 2024, while Canada has only seen 23 Prime Ministers and 29 ministries between 1867 and 2024. If Australia used the Canadian practice of counting only non-consecutive premierships as separate ministries, then Australia would recognise 37 ministries – which, even then, still shows the higher rate at which our Antipodean cousins churn through their Prime Ministers.

Australia has at least established a consistent method for measuring the lifespan of its ministries and published authoritative guides and lists which prevent any confusion. But the Parliament of Australia, rather than the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, seems to act as the official repository of this information and the official list of the current ministry and past ministries, which reflects how the Australians tie the life of a ministry to a prime minister and to a parliament. An official Australian source has published a guidebook and therefore eliminated all ambiguity.

However, their guidebook does not clearly explain what milestone marks the end date of a ministry in Australia. The Parliamentary Handbook records John Howard’s first ministry as going from 11 March 1996 (when the Governor General appointed him) to 21 October 1998 – which does not seem to mark any particular date of significance. According to the Parliamentary Handbook, the 38th Parliament opened on 30 March 1996 (which shows that the Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia takes office when the Governor-General appoints him and not based on any confirmation vote in the House of Representatives), “closed” (which probably means when the House of Representatives adjourned) on 12 July 1998, and was prorogued on 31 August 1998. But the general election took place on 3 October 1998, and the 1st session of the 39th Parliament convened on 10 November 1998. So what does this date of 21 October 1998 mean? My best guess is that it simply marks the moment where John Howard shuffled his cabinet after the election and advised the Governor-General to appoint any new ministers and re-commission him for his 2nd ministry. In other words, the ministry under this Australian method does not begin and end based on a vote in the House of Representatives but upon the date where the Governor-General first appoints a new prime minister or re-appoints an incumbent prime minister before opening the new parliament with a Throne Speech. Australia therefore emphatically does not employ confirmation voting, which usually explains why a polity would count separate ministries led by the same person for a continuous period.

Interestingly, David Brock and I showed in our recent article that the date on which the Governor General implements the incumbent prime minister’s cabinet shuffle after a general election has also has emerged as an important moment in Canada in 2019 and 2021 as well, not as the beginning of a new ministry but as what the Privy Council Office considers the end of the caretaker period. This shows a convergent evolution of sorts between Australian and Canadian constitutional conventions.

If Canada used the Australian method of tying ministries to both the prime minister and the parliament, then our list would look preliminarily something like this, though without knowing the exact dates on which post-election cabinet shuffles took place and when the Governor General would have re-appointed the incumbent prime minister, apart from in 2019 and 2021:

- Macdonald Ministry (1st): 1 July 1867 to 1872

- Macdonald Ministry (2nd): 1872 – 5 November 1873 (resignation mid-parliament)

- Mackenzie Ministry (1st): 7 November 1873 – 1874

- Mackenzie Ministry (2nd): 1874 – 8 October 1878

- Macdonald Ministry (3rd): 17 October 1878 – 1882

- Macdonald Ministry (4th) 1882 – 1887

- Macdonald Ministry (5th): 1887 – 1891

- Macdonald Ministry (6th): 1891 – 6 June 1891 (death)

- Abbott Ministry: 16 June 1891 – 24 November 1892

- Thompson Ministry: 5 December 1892 – 12 December 1894 (death)

- Bowell Ministry: 21 December 1894 – 27 April 1896 (resignation just after dissolution)

- Tupper Ministry: 1 May 1896 – 8 July 1896

- Laurier Ministry (1st): 11 July 1896 – 1900

- Laurier Ministry (2nd): 1900 – 1904

- Laurier Ministry (3rd): 1904 – 1908

- Laurier Ministry (4th) 1908 – 6 October 1911

- Borden Ministry (1st): 10 October 1911 – 12 October 1917

- Borden Ministry (2nd): 12 October 1917 – 10 July 1920

- Meighen Ministry: 10 July 1921 to 29 December 1921

- King Ministry (1st): 29 December 1921 – 1925

- King Ministry (2nd): 1925 – 28 June 1926 (forced resignation)

- Meighen Ministry (2nd): 29 June 1926 – 25 September 1926

- King Ministry (3rd): 25 September 1926 – 7 August 1930

- Bennett Ministry: 7 August 1930 – 23 October 1935

- King Ministry (4th): 23 October 1935 – 1940

- King Ministry (5th): 1940 – 1945

- King Ministry (6th): 1945 – 15 November 1948

- Laurent (1st): 15 November 1948 – 1949

- Laurent (2nd): 1949 – 1953

- Laurent (3rd): 1953 – 21 June 1957

- Diefenbaker (1st): 21 June 1957 – 1958

- Diefenbaker (2nd): 1958 – 1962

- Diefenbaker (3rd): 1962 – 22 April 1963

- Pearson (1st): 22 April 1963 – 1965

- Pearson (2nd): 1965 – 20 April 1968

- Trudeau (1st): 20 April 1968 – 1972

- Trudeau (2nd): 1972 – 1974

- Trudeau (3rd): 1974 – 3 June 1979

- Clark: 4 June 1979 – 2 March 1980

- Trudeau (4th): 3 March 1980 – 29 June 1984

- Turner: 29 June 1984 – 16 September 1984

- Mulroney (1st); 17 September 1984 – 1988

- Mulroney (2nd): 1988 – 24 June 1993

- Campbell: 25 June 1993 – 3 November 1993

- Chretien (1st): 4 November 1993 – 1997

- Chretien (2nd): 1997 – 2000

- Chretien (3rd): 2000 – 11 December 2003

- Martin (1st): 12 December 2003 – 2004

- Martin (2nd): 2004 – 5 February 2006

- Harper (1st): 6 February 2006 – 2008

- Harper (2nd): 2008 – 2011

- Harper (3rd): 2011 – 3 November 2015

- Trudeau (1st): 4 November 2015 – 20 November 2019 (post-election cabinet shuffle)

- Trudeau (2nd): 20 November 2019 – 26 October 2021 (post-election cabinet shuffle)

- Trudeau (3rd): 26 October 2021 – 2024 (ongoing)

Canada would have seen 55 Ministries since 1867 if we used the Australian method. Funnily enough, the current Albanese Ministry marks Australia’s 67th Ministry since only 1901 – which shows the enormous instability in their executive and tendency to oust party leaders.

Where Australia rejected the British-Canadian practice outright, New Zealand accepted but modified it. There the tenure of the prime minister determines that of the ministry as a whole, as in Canada and in the United Kingdom; the Cabinet Manual says that “the outgoing Prime Minister will advise the Governor-General to accept the resignation of the entire ministry.”[31] But the Kiwis now also refer to continuous stretches where one party remains in power under two or more prime ministers as the “nth party government.”[32] This practice seems to stretch back to the 1930s (at least retroactively), when New Zealand’s modern partysystem of Labour on the left and the Nationals on the right emerged. It might have gained new importance after New Zealand switched from single-member plurality to mixed-member proportional representation in 1996 and made coalition governments the norm.

For example, the “Sixth Labour Government of New Zealand” remained in office from 2017 to 2023, first under the ministry of Jacinda Ardern of 26 October 2017 to 25 January 2023 and later under the ministry of Chris Hipkins from 25 January to 27 November 2023.[33] Like in Canada, a ministry in New Zealand can span multiple parliaments. But the “nth party government” moniker emerged sui generis in New Zealand and has no equivalent in either Australia, Canada, or the United Kingdom. The New Zealand Gazette also officially records when the Governor-General of New Zealand appoints a Prime Minister and other cabinet ministers.[34] I like this idea, but the Canada Gazette does not record when the Governor General appoints a new Prime Minister and ministry; the Guide to Ministries to Confederation would serve as our closest equivalent public record.

New Zealand’s method would be like calling the Thatcher Ministry and the Major Ministry as together making up the “15th Conservative Government” from 1979 to 1997 (if we start with Robert Peel as the First Conservative Government in 1834), or the Blair Ministry and the Brown Ministry as the “6th Labour Government” from 2007 to 2010 (starting with Ramsay MacDonald in 1924). If Canada used this system, then the 1st Ministry of Sir John Alexander Macdonald of 1864 to 1873 would also be called “The First Conservative Government,” and the 2nd Ministry of Alexander Mackenzie of 1873 to 1878 would be called “The First Liberal Government.” But the 3rd Ministry, also headed by Sir John A. Macdonald from 1878 to his death in 1891, would combine with the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th Ministries of Abbott, Thompson, Bowell, and Tupper from 1891 to 1896 to become “The Second Conservative Government” from 1878 to 1896. Funnily enough, the Liberals and Conservatives have both formed 9 “Governments” under New Zealand’s method, but the Conservatives failed to win consecutive elections with their 2nd ministries within the period of their “Governments.” The Conservatives lost in 1896, 1921, and 1993, and they never succeeded in transferring power between themselves in their other 6 “Governments.”

Liberals

- Mackenzie (1873-1878)

- Laurier (1896-1911)

- King (1921-1926)

- King (1926-1930)

- King (1935-1948) & St. Laurent (1948-1957)

- Pearson (1963-1968) & Trudeau (1968-1979)

- Trudeau (1980-1984) & Turner (1984)

- Chretien (1993-2003) & Martin (2003-2006)

- Trudeau (2015-present)

Conservatives

- Macdonald (1864-1873)

- Macdonald (1878-1891), Abbott (1891-1892), Thompson (1892-1894), Bowell (1894-1896), Tupper (1896)

- Borden (1911-1920) & Meighen (1920-1921)

- Meighen (1926)

- Bennett (1930-1935)

- Diefenbaker (1957-1963)

- Clark (1979-1980)

- Mulroney (1984-1993) & Campbell (1993)

- Harper (2006-2015)

More confusingly still, the Kiwis also use “administration” over “ministry” in their Cabinet Manual:

“Since the introduction of New Zealand’s proportional representation election system, it has been the practice for a full appointment ceremony to be held when a government is formed after an election, even when the composition of the government has not greatly changed. The ceremony formally marks the formation and commencement of the new administration and marks the end of the caretaker period.”[35]

How I wish that I had caught that reference before David and I sent in our final manuscript to the Saskatchewan Law Review! The new constitutional convention emerging in Canada that the caretaker period ends upon the swearing if a new prime minister after an election or upon the incumbent prime minister’s first cabinet shuffle after an election also corresponds to New Zealand’s. However, New Zealand has at least adopted this new practice with good reason. Instead of undertaking a confirmation vote, the Governor-General still appoints or “re-appoints” a prime minister after each election but before the new parliament meets because the negotiations between the political parties in forming the coalition makes confirmation voting redundant. The appointment ceremony also makes a logical and transparent end of the caretaker period, since with a coalition in place, the prime minister will obviously command the confidence of the House of Representatives on the Address-in-Reply. In contrast, the Canadian convention has evolved for slightly more cynical, though still somewhat practical, reasons where the incumbent prime minister unilaterally declares the end of the caretaker period merely because none of the other parties publicly declared their intention to vote down the government on the Address-in-Reply.

While New Zealand’s Department of Minister and Cabinet maintains a “Ministerial List” of the current ministers and their portfolios, I could not find a definitive list equivalent to Canada’s Guide to Ministries Since Confederation and Australia’s “Current Ministry List” and “Former Ministry Lists” in its Parliamentary Handbook.

Since I could not find an authoritative governmental source equivalent to our Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation and notwithstanding my misgivings about the British equivalent, I had to refer to Wikipedia’s “List of Prime Ministers of New Zealand.” I believe that New Zealand has adopted its unique approach for two reasons: both because it has both churned through prime ministers quickly and yet also seen a series of several uninterrupted dynasties where since 1891 one party remains in power continuously under a succession of multiple leaders for many years. For example, a Liberal dynasty governed continuously from 1891 to 1912 under five different prime ministers and across 8 parliaments. And from 1891 to 2023, only one two occasions has one party remained in power only under one prime minister: Sir Walter Nash of the Labour Party from 1957 to 1960, and Sir Robert Muldoon of the National Party from 1975 to 1984. This entire pattern also suggests that the Labour and National Parties of New Zealand do not tolerate unpopular prime ministers and both prefer to try their luck with mid-parliamentary, intra-party transfers of power rather than presenting a deeply unpopular incumbent in the general election and risk losing by large margins. Canadian political parties could certainly draw some lessons here. But the Kiwis also seem subtler than their more overt cousins across the Tasman, because the Labour and National parliamentary parties of New Zealand have not become infamous for conducting brutal “spill votes” against their leaders like the Labour and Liberal parliamentary parties of Australia did against several of their leaders in the 2000s and 2010s.

The Realms which have practised Responsible Government the longest cannot all agree on something as apparently simple and straightforward as defining the duration of ministries and parties in power. Canada has preserved the original British definition that ties the ministry to the prime minister and ends only upon his resignation or death, which therefore recognises that a single ministry can span several consecutive parliaments. And Canada has also better articulated this method than the British, too, and bolstered it with good official sources. In contrast, Australia ties the ministry to both the prime minister and the parliament and therefore insists that while one parliament could contain more than one ministry, no ministry can span multiple consecutive parliaments. New Zealand has broadly accepted the British-Canadian definition that one prime minister heads a single ministry that can span multiple consecutive parliaments but then layered on a new concept to explain what happens when the same party remains in power consecutively for several years under two or more leaders.

Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have diverged from a common source, perhaps because of a few factors such as the maximum duration of the parliament, or perhaps due to something more random and arbitrary. Australia and New Zealand both set the maximum life of their parliaments at three years, compared to a maximum of seven years in the United Kingdom from 1715 to 1914, and a maximum of five years thereafter. The Parliament of Canada could live from a maximum of five years from 1867 to 2009, when the fixed-date election provision in the Canada Elections Act lowered its maximum lifespan to somewhere between four and year years. Alpheus Todd, the Librarian of the Parliament of Canada (both the Province and, after 1867, the Dominion) noted as early as the 1870s that the British Australasian colonies (including New Zealand) churned through premiers, and thus ministries, very quickly compared to in Canada; he attributed the comparative stability in Canada and the United Kingdom to the laws requiring ministerial by-elections, which British Australasia never had and which the United Kingdom and Canada eventually repealed in the early 20th century.[36]

But if Australia and New Zealand now share this trait of three-year parliaments in common and also share this common history of a quick churn of ministries, that would not explain why they have diverged from one another. Some other factor would have to pertain. This could point to something as arbitrary and happenstance as simply that Australia considers re-appointing incumbent ministries after a general election more democratic because of their pervasive republican mindset, or simply because this method acknowledges parliament in some fashion. But then again, Australia does not use confirmation voting, which makes their method redundant and asinine. New Zealand has layered on the original British approach instead of rejecting it by tying the ministry to the prime minister but also noting that one political party can remain in office for a continuous stretch under two or more leaders and prime ministers probably because its parliamentary parties do not allow unpopular prime ministers to cling to office and tank the party’s fortunes in the next general election. Unlike Australia’s arbitrary system, New Zealand’s makes sense and translates their precedents into a coherent rationale.

Only the Government of Canada has properly articulated and explained the method that the British also still use. In reality, the United Kingdom uses the same system as Canada and ties the ministry to the individual prime minister. However, the Cabinet Office has not published an authoritative and official list of British ministries since, say, the Act of Union of 1707, which has allowed wrong-headed editors on Wikipedia to exploit the ambiguity and devise their own false and faulty system of counting ministries more like the Australians. This method of counting “the First Johnson Ministry” of July to December 2019, in turn, directly contradicts the aforementioned testimony of electorally successful former prime ministers like Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair.

It’s all very interesting – at least to me and perhaps fifty others in the world. We only notice these differences when we study the Realms from the premise of commonality but not uniformity and acknowledge that these countries have grown and diverged in various ways from their shared inheritance.

Similar Posts:

Notes

[1] United Kingdom, Prime Minister’s Office, “Ministerial Appointments: July 2024,” 5 July 2024.

[2] United Kingdom, Prime Minister’s Office, “Featured,” accessed 9 July 2024.

[3] United Kingdom, Prime Minister’s Office, “State Opening of Parliament to Take Place on 17 July 2024,” 30 May 2024.

[4] Canada. Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, Henry F. Davis and André Millar. (Ottawa, Government of Canada, 1968): 77-79.

[5] Katherine Barber, editor Canadian Oxford Dictionary, Second Edition (Oxford University Press, 2004), at page 986, definition 4 of 5.

[6] The Privy Council Office’s Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation records only one exception to this rule, Privy Council Office, “Ninth Ministry, 10 October 1911 to 12 October 1917,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024;.

[7] Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Eighth Ministry: 6 February 2006 to 3 November 2015,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024. The Privy Council Office decided sometime after 2019 to count only the last full day of a ministry, but, in reality, the 28th Ministry lasted until 4 November and until a few minutes before Governor General Johnston swore in Justin Trudeau as head of the 29th Ministry.

[8] Privy Council Office, “First Ministry: 1 July 1867 to 5 November 1873,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Second Ministry: 7 November 1873 to 8 October 1878,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; O’Brien & Bosc, “Appendix 12: General Election Results Since 1867,” 1273.

[9] Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Sixth Ministry: 4 November 1993 to 11 December 2003,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Seventh Ministry: 13 December 2003 to 5 February 2006,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024;

[10] Privy Council Office, “Tenth Ministry, 12 October 1917 to 10 July 1920,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024.

[11] Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, 83-84.

[12] Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, “Constitutional Procedure Regarding a Change of Premier – Backgrounder,” 25 January 2013.

[13] Office of the Governor General of Canada, “Swearing-In Ceremony: Governor General Presided Over the Swearing-In Ceremony of the Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, Canada’s 23rd Prime Minister, and his Cabinet,” 4 November 2015, accessed 13 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Ninth Ministry, 4 November 2015 to Present,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023).

[14] Paul Martin in CBC Archives, “Paul Martin Concedes Defeat, Announces Resignation,” 23 January 2006.

[15] Office of the Governor General of Canada, “Date for the Swearing-in of the Honourable Stephen Harper as the 22nd Prime Minister and of his Cabinet,” 26 January 2006; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Seventh Ministry, 12 December 2003 to 5 February 2006,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023); Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Eighth Ministry, 6 February 2006 to 3 November 2015,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023).

[16] Privy Council Office, “Life of a Ministry: The Last Day,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation, 25 September 2023, accessed 13 March 2024.

[17] For example, Queen Elizabeth II invited Margaret Thatcher to form a government on 4 May 1979, one day after the general election held on 3 May 1979. Similarly, the Queen commissioned Tony Blair as Prime Minister on 2 May 1997, one day after the general election held on 1 May 1997. Margaret Thatcher recounts in her prime ministerial memoir that “We knew that we had won in the early hours of Friday 4 May, but it was not until the afternoon that we gained the clear majority of seats we needed – 44 as it eventually turned out.” Thatcher adds that the Palace called her around 2:45 p.m. and that the Queen asked her to form a government that same afternoon. Here Thatcher also demolishes the narrative in British Wikipedia and confirms that the British conform to the Canadian practice: “The Audience at which once receives the Queen’s authority to form a government comes to most prime ministers only once in a lifetime. The authority is unbroken when a sitting prime minister wins an election, and so it never had to be renewed throughout the years I was in office.” Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (Harper Collins, 1993), 17.

Tony Blair also notes in his autobiography: “On 2 May 1997, I walked into Downing Street as prime minister for the first time. […] The election night of 1 May had passed in a riot of celebration, exhilaration and expectation.” Tony Blair, A Journey: My Political Life (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopft), 3. Blair then recounts his first audience where the Queen asked him to form a government on pages 15-16, and he quoted the dialogue of Peter Morgan’s screenplay in the 2006 film The Queen.

[18] Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany, Articles 63 & 69; Reuven Y. Hazan, “Analysis: Israel’s New Constructive Vote of No-Confidence,” Knesset News, 18 March 2014; The Spanish Constitution, Articles 62(d) & 99(1-5) (Madrid: Agemcoa Estata Boletin Oficial del Estado, accessed October 2021) at pages 22 & 31; Scotland Act, 1998 (United Kingdom), c. 46, s. 46(1-4); Government of Wales Act, 2006 (United Kingdom), c. 32, s.46-47; Legislative Assembly and Executive Council Act (Nunavut), c. 5, s. 60; Legislative Assembly and Executive Council Act (Northwest Territories), c. 22, s. 61(1.1);

[19] The Instrument of Government, 1974: 152, at Articles 4-6.

[20] Northern Ireland Act, 1998 (United Kingdom), c. 47, s. 16A; Northern Irish Assembly, Standing Orders, Standing Order 44(1).

[21] J.W.J. Bowden, “The Origins of the Caretaker Convention: Governor General Aberdeen’s Dismissal of Prime Minister Tupper in 1896,” Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law 16, no. 2 (2022): 430-434.

[22] The United Kingdom. Cabinet Office, The Cabinet Manual: A Guide to Laws, Conventions and Rules on the Operation of Government, 1st Edition (London: Crown Copyright, October 2011), at paragraph 2.8 & endnote 10 of chapter 2.

[23] New Zealand. Cabinet Office, Cabinet Manual, 2023 (Wellington: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2023), at para. 6.48, and page 100.

[24] Martin Holland and Jonathan Boston, The Fourth Labour Government: Politics and Policy in New Zealand (Oxford University Press, 1990); Norton Fausto Garfield, The Fifth National Government of New Zealand (Anim Publishing, 2012).

[25] Parliament of Australia, Parliamentary Library, Parliamentary Handbook: Ministries, accessed 15 March 2024.

[26] The United Kingdom. Cabinet Office, The Cabinet Manual: A Guide to Laws, Conventions and Rules on the Operation of Government, 1st Edition (London: Crown Copyright, October 2011), at paragraph 2.8 & endnote 10 of chapter 2.

[27] Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (Harper Collins, 1993), 17.

[28] Tony Blair, A Journey: My Political Life (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopft), 3. Blair then recounts his first audience where the Queen asked him to form a government on pages 15-16, and he quoted the dialogue of Peter Morgan’s screenplay in the 2006 film The Queen.

[29] Norman Wilding and Philip Laundry, An Encyclopedia of Parliament (London: Cassell and Company,), 359-360.

[30] Parliament of Australia, Parliamentary Library, Parliamentary Handbook: Ministries, accessed 15 March 2024.

[31] New Zealand. Cabinet Office, Cabinet Manual, 2023 (Wellington: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2023), at para. 6.48, and page 100.

[32] Martin Holland and Jonathan Boston, The Fourth Labour Government: Politics and Policy in New Zealand (Oxford University Press, 1990); Norton Fausto Garfield, The Fifth National Government of New Zealand (Anim Publishing, 2012).

[33] Governor-General of New Zealand, “Swearing-in Ceremony Livestream,” 26 October 2017; Governor-General of New Zealand, “Appointment Ceremony of the New Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister,” 25 January 2023. In October 2017, Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy said that she “will exercise her reserve powers to appoint Jacinda Arden as Prime Minister and as an Executive Councillor.” I like that wording because it acknowledges that, strictly speaking, the Governor-General does not act on advice for the act of appointing a prime minister.

[34] The New Zealand Gazette, Vice-Regal: Appointment of Ministers, Notice Number 2023-vr5538, 28 November 2023.

[35] New Zealand. Cabinet Office, Cabinet Manual, 2008 (Wellington: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2008), at para. 6.46 and page 82.

[36] Alpheus Todd, Parliamentary Government in the British Colonies, 2nd Edition (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1894) at 61-63.