The Ministry Depends on the Prime Minister

The Governor General’s first constitutional duty is to appoint a Prime Minister and ensure the continuity of government. The Governor General usually appoints the leader of the political party which has either an outright majority or a plurality of MPs in the House of Commons, or barring that, the leader who can command a majority of the House of Commons at the time (like Alexander Mackenzie in November 1873), and only appoints a Prime Minister when the incumbent resigns, dies, or is dismissed from office. The tenure of the Prime Minister determines the tenure of the ministry as a whole; therefore, the Prime Minister’s resignation or death automatically forces the resignation of the entire ministry at once.[1] A single ministry can therefore span multiple parliaments, and a single parliament could include multiple ministries.[2] For instance, Stephen Harper’s 28th Ministry remained in office continuously from 6 February 2006 to 4 November 2015 and spanned the 39th, 40th, and 41st Parliaments elected in 2006, 2008, and 2011, respectively.[3] Alternatively, a single parliament might overlap with multiple ministries. The 2nd Parliament elected from July to October 1872, for instance, included two ministries because Sir John A. Macdonald resigned over the Pacific Scandal and Governor General Lord Dufferin appointed Alexander Mackenzie as the next Prime Minister in November 1873.[4] More recently, the 37th Parliament elected in 2000 saw an intra-party transition of power between the 26th and 27th Ministries of Chretien and Martin in December 2003.[5]

How Power Passes from One Ministry to the Next in Canada

In Canada, the transfer of power between ministries usually takes place two to three weeks after a general election or a political party’s leadership election as follows:

- The incumbent Prime Minister informs the Governor General that he intends to resign based on the results of the general or leadership election and becomes the “outgoing” Prime Minister;

- The leader of the party which won the largest number of seats, or the new leader of the incumbent party (whether an outright majority or only a plurality) becomes the “incoming” Prime Minister as the only plausible candidate;

- Within a few days, the Governor General formally recognizes the incoming Prime Minister as the “Prime Minister-designate” and asks him to prepare to form a government;

- The outgoing Prime Minister and Prime minister-designate agree to the exact timeline for the transition between their ministries;

- Finally, some two to three weeks later, the Governor General formally accepts the resignation of the outgoing Prime Minister and swears in the Prime Minister-designate as Prime Minister, along with the rest of the cabinet ministers in his ministry.[6]

The previous transfer of power between ministries in Ottawa happened in October and November 2015. On 19 October 2015, Canadians awarded the Liberals a parliamentary majority in the 42nd Parliament; the clear results of this general election made Conservative leader Stephen Harper the outgoing prime minister and Liberal leader Justin Trudeau the incoming prime minister that same night. The following day, on 20 October 2015, Stephen Harper informed Governor General David Johnston that he intended to resign as Prime Minister of Canada; Johnston summoned Justin Trudeau later that day and recognised him as the Prime Minister-designate. Finally, on 4 November 2015, the Governor General accepted the resignation of Stephen Harper, and thus that of the 28th Ministry as a whole, and subsequently swore in Justin Trudeau as Prime Minister along with the rest of the cabinet for the 29th Ministry.[7]

The transfer of power before the above took place in January and February 2006. On 23 January 2006, Stephen Harper’s Conservatives won only a plurality of seats. Prime Minister Paul Martin could therefore have decided to remain in office, try to win the support of the New Democrats and Bloc quebecois, and test the confidence of the new House of Commons; instead, he took to the podium to concede defeat and announced that he would resign as Prime Minister of Canada and as leader of the Liberal Party.[8] Consequently, Stephen Harper became the incoming prime minister and delivered a victory speech that same night. Governor General Michaelle Jean formally recognised Harper as the Prime Minister-designate three days later on 26 January 2006, and she formally accepted the resignation of Martin and the 27th Ministry and appointed Stephen Harper as Prime Minister and head of the 28th Ministry on 6 February 2006.[9]

This transition of two to three weeks allows the Governor General to appoint the new Prime Minister and the rest of the new ministry at the same time in one fell swoop.

Incumbent prime ministers have always thus far resigned shortly after their party’s leadership election so that the Governor General could appoint the new leader of the largest party in the House of Commons as the next prime minister – even in minority parliaments. For example, Lester Pearson announced in December 1967 that he intended to resign as prime minister after the Liberal Party elected a new leader. On 6 April 1968, the Liberals elected Pierre Trudeau, and on 20 April, Pearson resigned as prime minister had made way for Governor General Michener to appoint Trudeau as the next prime minister. Trudeau then advised the Governor General to dissolve parliament on 23 April. All this happened in a minority parliament where the Liberals held a large plurality of MPs in the House of Commons.[10]

After taking a famous walk in the snow, Pierre Trudeau announced on 29 February 1984 that he intended to resign the premiership after the Liberals elected their new leader. John Turner, a former Minister of Finance who resigned from Trudeau’s cabinet in 1974 over disagreements on wage-and-price controls and represented the right wing of the Liberal Party, won the leadership on 16 June 1984, even though he did not sit in the House of Commons at the time. (Something about this scenario sounds so familiar). On 30 June 1984, Pierre Trudeau resigned the premiership for the second and last time, and Governor General Jeanne Sauvé appointed Turner as the next prime minister.[11] The same scenario played out in 1993 when the Progressive Conservatives elected Kim Campbell as their new leader after Brian Mulroney.

From Justin Trudeau to Mark Carney

Justin Trudeau announced on 6 January 2025 that he had had advised the Governor General to prorogue parliament until 24 March 2025 so that the Liberal Party would hold its leadership election. Trudeau added that he also “intends to resign as party leader and as prime minister after the [Liberal] party selects its next leader.”[12] However, Trudeau phrased his speech to make the prorogation on the one hand and his intention to resign as unrelated; officially, he simply wanted to end “the longest session of a minority Parliament in Canadian history” which had “been paralyzed for months” and the intersession would then by pure coincidence would also enable the Liberal Party to elect a new leader in the typically convoluted Canadian fashion.

Trudeau indicated in a press conference on 4 March 2025 that he would coordinate with the new Liberal leader after the leadership election on 9 March but expected that the transfer of power “should happen reasonably quickly.”

30:18. Hi, Prime Minister, Rachel Haynes from CTV National News. As we know, the Liberal Party is going to be picking a new leader over the weekend. But when is it going to be your last official day as prime minister?

Trudeau: Uh, that will be, uh, up to a conversation between, uh, the new leader and myself to figure out what – how long a transition is needed. Um, it, uh, it should happen reasonably quickly but there’s, uh, a lot of things to do in a transition like this, particularly at this complicated time in the world.

Ma dernière journée sera déterminée une fois que le nouveau chef du parti libéral sera choisi. Uh, c’est une conversation sur, uh, combien de temps va être nécessaire pour la transition. Il y a énormément d’éléments à considérer, mais je sais qu’on veut faire ça assez rapidement.[13]

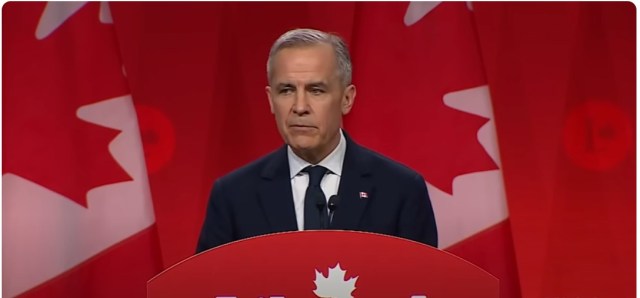

On 9 March 2025, Mark Carney won the Liberal leadership resoundingly on the first ballot with fully 86% of the votes of Liberal members.[14] Chrystia Freeland won a paltry 8% of the vote and learned the hard way that the assassin never wears the Crown; she could have spared herself the embarrassment if she had read The Prince or even Michael Dobbs’s House of Cards.

As of 10 March, The Globe and Mail reported that Carney “is not expected to officially be sworn in as prime minister until later in the week” – i.e., this week.[15] That would make a very short transition indeed of around only one week, when these things typically take three to prepare. As of 6:00 pm on 10 March, the press has not reported on whether Governor General Mary Simon has yet met with Mark Carney and officially named him Prime Minister-designate.

The Globe and Mail also reported that Carney would aim for a general election on “either [Friday] April 28 or [Saturday] May 5”, which coupled with the minimum writ of 36 days would mean that Carney would have to advise the Governor General to dissolve this 44th Parliament and finally put it out of its misery on Sunday, 23 March for the polling day in April or Sunday, 30 March for the polling day in May. Under this scenario, Carney would serve as Prime Minister for only one or two weeks before facing the electorate.

From a political standpoint, this seems like the best option given that he does not sit in the House of Commons and needs to get elected himself. Alternatively, he would have to advise the Governor General to summon a 2nd session of this rotten parliament that must be dissolved by September for an election in October anyway, and then endure the indignity of forcing the Government Leader in the House of Commons to stand in for him during the debates on the Address-in-Reply. Parliament would probably not have enough time to enact supply before public monies start to run out at the start of the new fiscal year on 1 April. But a general election, and only a general election, would solve that problem: Governor General’s Special Warrants can defray the expenses of the Government of Canada during the writ and only for up to 60 days after the date fixed for the return of the writs.[16] The Government of Canada last issued Special Warrants in 2006 and 2011 because general elections held in those years meant that the new parliaments did not convene until after the new fiscal year began on 1 April.[17]

The Pawley Precedent of 1988 and the Giorno Plan of 2025

Guy Giorno suggested in late January an alternative scenario where Justin Trudeau would continue serving as an outgoing, caretaker prime minister during the election – almost like an American president at the end of his second term in office – instead of making way for the new Liberal leader to become Prime Minister right away.[18] In Giorno’s estimation, Trudeau could (presumably still in consultation with Carney) advise the Governor General to dissolve Parliament in March, unburden Carney from what has been, and allow Carney to lead the Liberals as his own man in the election. Trudeau would then resign at some point shortly after the election in any case, and Governor General Mary Simon would commission either Mark Carney or Pierre Poilievre as the next Prime Minister of Canada based on the results. No federal precedent exists to support this method.

However, Giorno pointed to an interesting provincial precedent from Manitoba in 1988 to support his suggestion:

It would be constitutionally proper for Trudeau to act in this manner, and there is a precedent. When Gary Doer was elected to lead the governing Manitoba New Democrats in 1988, he did not become premier. The incumbent NDP premier, Howard Pawley, chose not to tender his resignation to the lieutenant-governor. Instead, Pawley remained in office during the general election, while observing the caretaker convention. When he ultimately resigned, the lieutenant-governor commissioned Progressive Conservative leader Gary Filmon, whose party had won a plurality of seats, to form a new government. (In that instance, dissolution had occurred, and a general election was already underway when the NDP elected its new leader. Nonetheless, the example demonstrated that what vacates the office of a first minister is not a partisan leadership contest but the incumbent’s resignation.)

But Giorno glossed over the strange details of this inauspicious and peculiar precedent that provides nothing worth emulating elsewhere.

Howard Pawley’s New Democrats had won a small majority of 30 out of 57 seats in the legislative assembly in the previous election in 1986. In that assembly, 29 MLAs constituted an arithmetic majority, and since the governing party usually puts up a speaker, the practical majority rises to 30. A cabinet minister resigned in February 1988 and left the Pawley government with only 29 MLAs and no room for error. But on 8 March 1988, New Democratic MLA Jim Walding, who had served as Speaker in the previous legislature from 1982 to 1986, lashed out at the Pawley government from the backbenchers, voted against the budget that spring, and forced an early election.[19] This shocking defeat shattered Howard Pawley to such an extent that he announced the following day on 9 March that Manitobans would have to go to the polls on 26 April 1988 and that he would resign as the party leadership after New Democrats elected his successor on 31 March during the election and that he would not seek re-election in his own riding.[20]

Pawley’s defeat caught everyone off guard. Pawley had to advise the Administrator of the Government of Manitoba, Alfred Monnin (also Chief Justice of the Manitoba Court of Appeal), to dissolve the legislature because Lieutenant Governor George Johnson was vacationing in Florida at the time.[21] Pawley’s government had by then become deeply unpopular, and many New Democratic voters had defected to the resurgent Liberals because of various scandals and high public automotive insurance rates. Pawley believed that he would have led the New Democrats into electoral oblivion if he remained as leader, but that his resignation would at least give the New Democrats the chance to remain “an effective opposition” in the next legislature.[22] New Democrats in Manitoba then voted by phone on 30 March and elected Urban Affairs Minister Gary Doer on the third ballot.[23]

The Globe and Mail reported on 29 March that “the new NDP leader […] will succeed Howard Pawley as the premier of Manitoba” and again on 31 March that Pawley would tender his resignation as premier later that day so that the Lieutenant Governor could appoint Gary Doer as the next premier during the election in a repeat of what Senator Sir Mackenzie Bowell and Sir Charles Tupper did in 1896.[24] The New Democratic Party of Manitoba even bought advertisements saying that the party members were “choosing ‘a new premier for Manitoba’ at its leadership convention.” But “Gary Doer […] persuaded Howard Pawley to abandon his plan to resign before the April 26 provincial election”, and Pawley decided instead to “remain as a caretaker premier.” Howard Pawley and Gary Doer visited the Lieutenant Governor together for about ten minutes on 31 March, where Pawley agreed to remain premier until after the election. Norman Ward, then a Professor emeritus of Political Science at the University of Saskatchewan, praised Gary Doer for having prevented a potential constitutional crisis.[25]

Perhaps Giorno did not study all the details of this precedent very closely; at the very least, he did not present these details to his readers in The Hub. I myself remained totally unaware of this precedent until after having read Giorno’s essay, and I’m glad to have looked into it yet further to glean any potential lessons from it. That last detail where Pawley had originally intended to resign the premiership during the election in the hope that the Lieutenant Governor would also appoint Gary Doer as the next Premier of Manitoba during the election does not fit into the scenario that Giorno advocated. And in another amusing irony, Giorno quoted favourably from my work outlining how Governor General Lord Aberdeen forced Sir Charles Tupper to resign as Prime Minister by rejecting his constitutional advice to summon Senators and appoint judges yet missed the most relevant similarity between my article “The Origins of the Caretaker Convention: When Governor General Lord Aberdeen Dismissed Prime Minister Tupper in 1896” and his idea that Trudeau should stay on as prime minister during the election. Incumbent Prime Minister Senator Sir Mackenzie Bowell resigned as Prime Minister of Canada on 27 April 1896, three days after he had advised Governor General Lord Aberdeen to dissolve the 7th Parliament; Aberdeen then commissioned the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, Sir Charles Tupper, as Prime Minister on 1 May 1896 during the election.[26]

Giorno’s plan would rely on Carney’s personal powers of persuasion over Trudeau, Carney’s confidence that he would eventually lead the Liberals to victory and earn the right to become prime minister, and on Carney’s restraint to shun the trappings of political power. Carney would have to convince Trudeau to advise the Governor General to dissolve Parliament by the end of the March, which would, in turn, free Carney to run as his own man and allow him to focus entirely on leading the Liberals to victory instead of also governing as Prime Minister. Perhaps this scenario would help the Liberals by throwing Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives off balance.

The Convention Scenario for Transferring Power from Trudeau to Carney

But so far, neither Justin Trudeau nor Mark Carney has expressed any interest in following the Giorno Plan. We can therefore expect that the transfer of power will happen within the next week or so in accordance with the normal Canadian method. Trudeau and Carney have presumably already by now met to determine the best date for the formal transfer of power. Outgoing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would inform Governor General Mary Simon of this plan (which he might have already done), and Her Excellency would invite Mark Carney for an audience and formally name him prime minister-designate within the next day or two. Perhaps one week after that – since Trudeau and Carney want a quick turnaround – the Governor General would then formally accept Trudeau’s resignation and formally appoint Mark Carney and swear in the rest of his cabinet as the 30th Canadian Ministry since Confederation at Rideau Hall.

Similar Posts:

- Why John Turner “Had No Option” in 1984 (January 2025)

- Justin Trudeau Had An Epiphany and Endorsed My Doctrine on Prorogation (January 2025)

- All I Want for Christmas Is a Constitutional Crisis (December 2024)

- Ousting Party Leaders: From the King Doctrine to the Unenforceable Reform Act (October 2024)

- “I Had No Option”: How John Turner Became Pierre Trudeau’s Patronage Patsy in 1984 (September 2024)

- The Commonwealth Realms Diverge: Whether the Prime Minister Determines the Life of the Ministry or Not (July 2024)

- Replacing the Prime Minister During an Election: A Forgotten Canadian Precedent (June 2024)

- Justin Trudeau Has Made Prorogation Great Again (October 2020)

Notes

[1] Canada. Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, Henry F. Davis and André Millar. (Ottawa, Government of Canada, 1968): 77-79.

[2] The Privy Council Office’s Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation records only one exception to this rule, Privy Council Office, “Ninth Ministry, 10 October 1911 to 12 October 1917,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024;.

[3] Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Eighth Ministry: 6 February 2006 to 3 November 2015,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024. The Privy Council Office decided sometime after 2019 to count only the last full day of a ministry, but, in reality, the 28th Ministry lasted until 4 November and until a few minutes before Governor General Johnston swore in Justin Trudeau as head of the 29th Ministry.

[4] Privy Council Office, “First Ministry: 1 July 1867 to 5 November 1873,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Second Ministry: 7 November 1873 to 8 October 1878,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; O’Brien & Bosc, “Appendix 12: General Election Results Since 1867,” 1273.

[5] Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Sixth Ministry: 4 November 1993 to 11 December 2003,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Seventh Ministry: 13 December 2003 to 5 February 2006,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (25 September 2023), accessed 15 March 2024;

[6] Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, 83-84.

[7] Office of the Governor General of Canada, “Swearing-In Ceremony: Governor General Presided Over the Swearing-In Ceremony of the Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, Canada’s 23rd Prime Minister, and his Cabinet,” 4 November 2015, accessed 13 March 2024; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Ninth Ministry, 4 November 2015 to Present,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023).

[8] Paul Martin in CBC Archives, “Paul Martin Concedes Defeat, Announces Resignation,” 23 January 2006.

[9] Office of the Governor General of Canada, “Date for the Swearing-in of the Honourable Stephen Harper as the 22nd Prime Minister and of his Cabinet,” 26 January 2006; Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Seventh Ministry, 12 December 2003 to 5 February 2006,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023); Privy Council Office, “Twenty-Eighth Ministry, 6 February 2006 to 3 November 2015,” in Guide to Canadian Ministries Since Confederation (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 25 September 2023).

[10] J.W.J. Bowden, “How Governors General Appoint Prime Ministers: Why John Turner Believed That He ‘Had No Option’ and Became the Patronage Patsy of 1984,” Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law 18, no. 3 (2024): 745-746.

[11] Bowden, “How Governors General Appoint Prime Ministers,” 715.

[12] National Post, “Read the Full Text of Justin Trudeau’s Resignation Speech,” 6 January 2025.

[13] CPAC, “PM Justin Trudeau Reacts to U.S. Tariffs, Outlines Government’s Response – March 4, 2025,” streamed on 4 March 2025.

[14] Catherine Lévesque, “Mark Carney Wins Liberal Leadership by a Landslide with 86% of Votes,” National Post, 9 March 2025.

[15] Robert Fife and Stephanie Levitz, “Mark Carney Meets with Outgoing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to Sort Out Transition Plan,” The Globe and Mail, 10 March 2025.

[16] Financial Administration Act R.S.C., 1985, c. F-11, at section 30; Government of Canada, Treasury Board Secretariat, “Governor General’s Special Warrants,” 19 October 2015.

[17] Government of Canada, Treasury Board Secretariat, “Governor General’s Special Warrants (for the fiscal years ending March 31, 2006 and March 31, 2007),” 7 October 2008; Government of Canada, Treasury Board Secretariat, “Statement on the Use of Governor General’s Special Warrants for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2012,” December 2011.

[18] Guy, Giorno, “The Next Federal Election Will Be Anything But Ordinary. Here Are the Important Constitutional Questions to Consider,” The Hub, 25 January 2025.

[19] Christopher P. Adams, Politics in Manitoba: Parties, Leaders, and Voters (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2008), 125.

[20] Ian Stewart, Just One Vote: From Jim Walding’s Nomination to Constitutional Defeat (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2009), 153.

[21] The Globe and Mail, “Pawley Quits as Vote Is Set for April 26 in Manitoba,” 10 March 1986, at A1.

[22] Gregory Marchildon, “Howard Pawley, 1981-1988,” chapter 16 in Manitoba Premiers of the 19th and 20th Centuries, edited by Barry Ferguson and Robert Alexander Wardhaugh, 331-353, (Regina: University of Regina-Canadian Plains Research Centre Press, 2010), 348.

[23] Richard Cleroux and Geoffrey York, “Doer Favored to Win Manitoba NDP Leadership Race,” The Globe and Mail, 15 March 1988; Geoffrey York, “Doer Captures NDP Helm in Tight Manitoba Race,” The Globe and Mail, 31 March 1988, at pages A1, A4.

[24] Geoffrey York, “NDP Delegates Pick Leader Tomorrow,” The Globe and Mail, 29 March 1988, at A4; Geoffrey York, “Doer Captures NDP Helm in Tight Manitoba Race,” The Globe and Mail, 31 March 1988, at A1, A4.

[25] Geoffrey York, “Pawley to Stay Premier Until Manitoba Election,” The Globe and Mail, 1 April 1988, at A3.

[26] J.W.J. Bowden, “The Origins of the Caretaker Convention: When Governor General Lord Aberdeen Dismissed Prime Minister Tupper in 1896.” Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law 16, no. 2 (2022): 395.