Overall Impressions on the Discussion

I thank my friend Phil Lagassé for having invited me to speak on government formation and the caretaker convention to his seminar on parliamentary government and parliamentary reform on 25 January 2015. I’ve uploaded my original, English-language PowerPoint here to Parliamentum. I was obliged to give most of my presentation in French, which I found difficult, though it went better than I had expected.

I was very surprised that none of the students objected to the premise of “No Discretion: On Prorogation and the Governor General,” the old article that Nick MacDonald and I wrote over five years ago which set me off on this constitutional odyssey. Resigned agreement or even a tacit endorsement of those views would have been inconceivable a few years ago. It wasn’t because they supported prime ministerial authority per se, but rather because they really didn’t want to support any reforms that would force the Governors to play a more active role. In Belgium, for instance, there are well-established conventions on the King’s role in forming governments that run afoul of the norms in Canada and the United Kingdom – though as New Zealand post-1996 shows, these conventions would necessarily change to some extent in the Realms, too, if coalition government became the norm. (Australia is a special case, because the Liberals and Nationals are two ideological compatible parties in a perpetual coalition that doesn’t require much coaxing from the Crown).

More fundamentally, I would at this stage also attribute this shift to two main factors. First, subsequent experience has validated our argument, particularly in Ontario, where initially Lieutenant Governor Onley and now Lieutenant Governor Dowdeswell have explicitly endorsed the view which we promoted: “In Canada, by convention, the Crown must accept the advice of the First Minister concerning prorogation.” (Someone once asked me if I had been consulted on or wrote this material and interpretation. I was not consulted on it and did not write it, but I do agree with it and regard it as an accurate description of the practice and procedure based on all the historical evidence). Scholars can object as strenuously and as stridently as they like, but these are the facts established by history and accepted as constitutional practice. One can make a normative critique of this system and propose reforms, but one cannot deny the facts and then pretend to be engaging in the descriptive. Second, the passage of time has borne out one of my other suspicions: most of the criticism of Harper’s early dissolution of 2008 and prorogations of 2008 and 2009 were partisan criticisms masquerading as process arguments on constitutional procedures. (There’s nothing wrong with partisan criticism of an incumbent government, but it is mendacious to disguise such criticisms as a principled constitutional argument). Now that the Conservatives must content themselves with playing the role of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition in this 42nd Parliament and that Justin Trudeau has succeeded Stephen Harper as Prime Minister of Canada, we can assess Harper’s executive decisions more rationally without the stream of abuse that normally accompanied such discussions even as recently as this time last year. At least one scholar accused me of being an apologist for Harper, and some provincial Conservatives in Ontario accused me of the same with respect for Premier McGuinty after his tactical prorogation in October 2012. In fact, I am not an apologist for any political party; instead, I defend the principles and practices of executive authority within Canada’s system of government – irrespective of whatever party happens to form government.

In addition, I’ve long noted that the Two Solitudes of Canada even show themselves in the scholarship on the Crown’s executive authority, particularly the Governors’ discretionary authority to reject ministerial advice, often called the “reserve power.” The well-established constitutional scholars in Quebec – such as Henri Brun, Guy Tremblay, Eugénie Brouillet, and to some extent Louis Massicotte (based on our CSPG panel last week) – oppose in principle and downplay in practice the notion that a governor could or should ever reject a first minister’s advice to dissolve parliament. One of the few French-speaking Quebec scholars who conforms more to the English-language schools of thought is Hugo Cyr. If memory serves, Cyr even referred to the aforementioned four scholars, who are all from Université Laval, as “The Laval School” at Peter Russell’s workshop on constitutional conventions on 3 February 2011 when he contrasted his own views to theirs. Some of Phil’s students identified as republican in outlook (and they also fully acknowledged the normative nature of that view in the Canadian context, which as a realist, I greatly appreciate) and therefore did not approve in principle of reforming the Canadian system along, say, the lines of Belgium where the King necessarily plays an active role in government formation.

The Principles of Government Formation in Canada

Presentation: Government Formation

1. Responsible Government

Government formation hinges upon the executive authority of the Crown. The Queen appoints the Governor General upon the advice of the Prime Minister. The Governor and Prime Minister both derive their executive authority from the Crown. The Governor General appoints the Prime Minister based on the authority that the Letters Patent have delegated to him[1], and the Prime Minister and ministry as a whole takes responsibility for all acts of the Crown promulgated in the name of the Queen.[2]

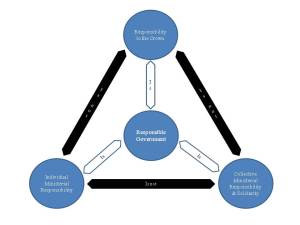

At its core, Responsible Government is a trinity (three in one) of responsibilities: ministerial responsibility to the Crown, individual ministerial responsibility before the Commons, and collective ministerial responsibility & solidarity before the Commons.[3] Responsible Government means that “Ministers of the Crown take responsibility of all acts of the Crown”[4] and that the Governor General acts on and in accordance with ministerial advice, save for exceptional circumstances.[5] In this manner, Responsible Government therefore preserves and fully incorporates the medieval principle of Royal Infallibility and reconciles it with popular rule and universal adult suffrage. The Queen can still do no wrong because it is the ministry which takes responsibility for all acts of the Crown, for good or ill. The Governor General can only refuse to promulgate ministerial advice in exceptional circumstances because the consequence of exercising such discretionary authority is equally and proportionately exceptional: the Governor General thereby dismisses the Prime Minister and ministry which tendered the original constitutional advice and must appoint in their place a new Prime Minister and ministry which can then take responsibility for the Governor’s decision to refuse advice and force the dismissal of their predecessors.[6]

Eglington referred to Responsible Government as a trinity, so I thought that I would make my down diagram representing the nature and aspects of Responsible Government based on the sorts of diagrams that illustrate the Holy Trinity and the three aspects of God in small-o orthodox Christianity

In addition, the first duty of the Governor General is to ensure that there is always a duly-appointed ministry in office because the Queen’s business must always carry on.[7] Put simply, there must always be and is always a ministry in office. At no point is there an “interregnum” in of the office of prime minister. In addition, the tenure, or term in office, of the prime minister determines the tenure of the ministry as a whole; the prime minister’s resignation automatically entails the resignation of the ministry as a whole.[8] For example, Stephen Harper’s term as prime minister extends from the day on which Governor General Michaelle Jean appointed him, on 6 February 2006, to the day on which he formally tendered his resignation to Governor General David Johnston on 4 November 2015.

- The Confidence Convention

The confidence convention therefore takes on a broader meaning than most contemporary scholars would summarize it. Most commonly, they will define the confidence convention as something to the effect, “The government must command the confidence of the House of Commons”; they might add something like, “if the government loses the confidence of the Commons, then either there would be a new government (through a mid-parliamentary transition of power) or a new parliament (through dissolution and fresh elections).” These statements are both truth – but they’re also incomplete and gloss over some crucial aspects of Responsible Government. They’re truth, but they’re not the whole truth.

The ministry must command the confidence of the Commons. Once the ministry has demonstrated that it commands the confidence of the Commons, it continues to hold that confidence until the moment that the Commons decides to withdraw it from the ministry.[9] Generally, the Address in the Reply to the Speech from the Throne acts as the first de facto confidence measure in a new session of parliament, which means that the ministry would command the confidence of the Commons if the Address in Reply passes. That said, the ministry can also judge when it has lost the confidence of the Commons, such as by deeming a bill or motion a matter of confidence and then losing a vote on it, or if it has, more generally, lost the ability to control the agenda of the Commons.[10]

But at select intervals, the ministry’s command of the confidence of the Commons is a sufficient condition and not a necessary condition. Logically, it cannot possibly be true that the ministry always commands the confidence of the Commons — because sometimes the Commons doesn’t exist (as in when Parliament is dissolved), and because sometimes the governor general promulgates the prime minister’s constitutional advice when the ministry has explicitly lost the confidence of the Commons (as with early dissolution in some minority parliaments).

First, the governor general expresses confidence in the prime minister by appointing him and granting him an official commission of authority to govern, which allows him to form a ministry. Second, the Commons either confirms that it also holds confidence in the ministry, or it expresses non-confidence in the ministry.

Most of the discussions surrounding Harper’s use of executive authority and early dissolution and prorogation between 2008 and 2010 glossed over this significant fact: if the Commons withdraws its confidence from the ministry, this does not automatically mean that the Crown also withdraws its confidence from the Ministry, which explains why the incumbent prime minister can advise — and apart from exceptional circumstances — receive, an early dissolution. If it were true that the governor general automatically withdraws his confidence from the prime minister and revokes his authority to govern as soon as the Commons withdraws its confidence from the ministry, then there would be no such thing as early dissolution, and there would instead only be mid-parliamentary transitions of power.

However, if the governor general refused to promulgate the prime minister’s advice to dissolve parliament, then would in so doing withdraw his confidence from the prime minister and revoke his authority to govern. At that stage, the governor general would then have to appoint a new prime minister and ministry who could take responsibility for these acts of the Crown (refusing the dissolution and dismissing the previous ministry), because a ministry can only take responsibility for advice that it has offered, not for the contrary advice that it did not offer.

- Constitutional Entrenchment of Executive Authority

Prorogation and dissolution are constitutionally entrenched executive authorities under sections 38 and 50, respectively, of the Constitution Act, 1867, which means that only a constitutional amendment pursuant to section 41(a) of the Constitution Act, 1982 could abolish this executive authority and transfer it to a constitutional provision. Prime Minister Trudeau outlined in Daniel Leblanc’s mandate letter that he should “change the House of Commons Standing Orders to end the improper use of omnibus bills and prorogation.” While the House of Commons could easily amend its Standing Orders in order to better regulate omnibus bus, the Standing Orders could not restrict the executive authority over prorogation because they would then be ultra vires of the Constitution Acts. (I’ve covered this issue in a previous entry, too). The House of Commons has the authority to manage its internal affairs, but its Standing Orders cannot supersede the constitution; more fundamentally, prorogation and dissolution are executive authorities, not parliamentary ones. Simply because they affect the conduct of parliament does not make them legislative authorities.

Parliament therefore cannot limit the prime minister’s discretion to advise and take responsibility for prorogation or dissolution without also necessarily limiting how the Governor promulgates that advice — because Responsible Government means that ministers take responsibility for all acts of the Crown, not that the Governor General practises a form of personal rule that would please a Stuart King. The Governor and First Minister form a chain of authority and ultimately both derive their commissions from the Queen.[11]

The law cannot drive a wedge between the Governor General and the Prime Minister. The law cannot limit the authority of the First Minister without also necessarily limiting the authority of the Governor, because the First Minister derives his authority as First Minister, i.e., role of the Crown’s primary constitutional adviser, by virtue of the Governor’s commission of appointment and confidence in him.

- The Steps Involved in a Transition of Power from One Ministry to Another

In Canada, transitions of power between ministries normally last two to three weeks and follow this general procedure. I shall remain eternally grateful to Lieutenant Governor Onley of Ontario for having published all of this information on the Lieutenant Governor’s website for public consumption.

- Incumbent first minister informs the governor of his intention to resign and becomes the “outgoing” first minister

- The party leader poised to become the next first minister then becomes the “incoming” first minister

- A few days later, the governor summons the incoming first minister, who then becomes the first minister-designate

- The outgoing first minister and first minister-designate agree to the exact timeline for the transition.

- 2 to 3 weeks later, the governor formally appoints the first minister-designate to office as first minister and swears in the rest of the cabinet

At the time, Lieutenant Governor Onley made clear that the intra-party, mid-parliamentary transition between the McGuinty and Wynne ministries occurred along the following timeline.

- 12 October 2012: Premier McGuinty announced his intention to resign. The Liberal Party of Ontario then held an election amongst its members to elect a new party leader.

- 26 January 2013: The Liberal Party elected Kathleen Wynne as its new leader.

- 31 January 2013: Lieutenant Governor Onley recognized Wynne as Premier-designate. McGuinty & Wynne then coordinated transition.

- 11 February 2013: McGuinty resigned, and Onley appointed Wynne as Premier.

If we apply those procedures to the most recent federal general election of 2015, we would derive the following steps. This transition proved straightforward because the voters gave the Liberals a parliamentary majority, and because it occurred after an election when parliament was dissolved rather than mid-parliament, as the aforesaid example in Ontario did.

- 19 October 2015: Canadians elected members for the 42nd Parliament. The Liberals won a parliamentary majority. Harper then became the outgoing prime minister & Trudeau became the incoming prime minister.

- 20 October 2015: Harper informed His Excellency that he intended to resign. Governor General Johnston summon Justin Trudeau later that day and made him Prime Minister-designate.

- 4 November 2015: Harper resigned as prime minister, and the 28th Ministry went along with him. Governor General Johnston then appointed Justin Trudeau as Prime Minister and swore in the Cabinet for the 29th Ministry.

- The Caretaker Convention

The Government of Canada’s official position is set out in the Guidelines on the Conduct of Ministers, Ministers of State, Exempt Staff and Public Servants During an Election.

“[D]uring an election, a government should restrict itself – in matters of policy, expenditure and appointments – to activity that is: a) routine, or b) non-controversial, or c) urgent and in the public interest, or d) reversible by a new government without undue cost or disruption, or e) agreed to by the Opposition (in those cases where consultation is appropriate).”

The Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada of 1968 refers to this concept as “the principle of restraint.”

1.[…] The extent of these restraints varies according to the situation and to the disposition of the Government to recognize them.

2. The possibility of restraint only arises if the continuation of confidence in the Government is called into question. A defeat in the House preceding dissolution or a defeat at the polls would be the usual causes of restraint.

3. The restraint has been recognized as applying to important policy decisions and appointments of permanence and importance. Urgent and routine matters necessary for the conduct of government are not affected.[12]

- The Prorogation-Coalition Controversy of 2008 As Case Study

As Nick MacDonald and I pointed out in our little article from 2011, a first minister’s advice to prorogue the assembly has never been refused since Responsible Government emerged in the 1840s.

Even if a governor tried to make a stand and break centuries of precedent, he would, in refusing a first minister’s advice to prorogue, force his resignation and then have to appoint a new first minister who could take responsibility for the advice not to prorogue. Therefore, if Governor General Jean had refused Prime Minister Harper’s advice to prorogue the 1st session of the 40th Parliament on 4 December 2008, she would have, in so doing, forced Harper to resign and then had to appoint Stephane Dion as prime minister.

Similar Posts:

- Caretaker Convention

- Confidence Convention

- Appointment of the Prime Minister

- Prorogation

- Dissolution

[1] Christopher McCreery, “Myth and Misunderstanding: The Origins and Meaning of the Letters Patent Constituting the Office of the Governor General 1947,” Chapter 3 in The Evolving Canadian Crown, edited by Jennifer Smith and D. Michael Jackson, 31-56 (Montreal-Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011), 32. As McCreery shows, the Queen of the Canada – not the Governor General – remains the source of the constitutional powers and authorities by virtue of section 9 of the Constitution Act, 1867. This is why Letters Patent have delegated, not transferred, authority from the Queen, who personifies the Crown, to the Governor General, who represents the Queen.

[2] Sir John George Bourinot, Parliamentary Procedure and Practice, 4th ed. (Montreal: Dawson Brothers Publishing, 1916): 102.

[3] Robert Macgregor Dawson. “The Constitutional Question.” Dalhousie Review VI, no. 3 (October 1926): 332-337; Eugene Forsey and Graham C. Eglington, The Question of Confidence in Responsible Government (Ottawa: Parliament of Canada, 1985), 16-17.

[4] Sir John George Bourinot, Parliamentary Procedure and Practice, 4th ed. (Montreal: Dawson Brothers Publishing, 1916): 102.

[5] R. Macgregor Dawson, The Government of Canada. 5th ed. (1970), revised by Norman Ward (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1947): 175.

[6] Sir John George Bourinot, Parliamentary Procedure and Practice. 1st ed. (Montreal: Dawson Brothers Publishing, 1884): 58.

[7] Canada. Department of Canadian Heritage. Ceremonial and Protocol Handbook. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, c. 1998): G.4-2; Henri Brun, Guy Tremblay, and Eugénie Brouillet, Droit constitutionnel. 5th Ed. (Montreal : Éditions Yvon Blais, 2008): 371.

[8] Canada. Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, Henry F. Davis and André Millar. (Ottawa, Government of Canada, 1968): 77-79.

[9] Peter Neary, “Confidence: How Much Is Enough?” Constitutional Forum constitutionnel 18, no. 1 (2009): 51-54; United Kingdom. Cabinet Office, The Cabinet Manual — Draft: A Guide to Laws, Conventions and the Rules on the Operations of Government. (London: Crown Copy-right, December 2010): 25.

[10] Philip Norton, “Government Defeats in the House of Commons: The British Experience,” Canadian Parliamentary Review (Winter 1985-1986): 6.

[11] Eugene Forsey and Graham C. Eglington, The Question of Confidence in Responsible Government (Ottawa: Parliament of Canada, 1985), 13-14.

[12] Canada. Privy Council Office, Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada, Henry F. Davis and André Millar.(Ottawa, Government of Canada, 1968): 89.

Congratulations James on another superb Article and Presentation. I will point out that historically there have been a few ‘Prime Ministerial Interregnums’ in Canada. There were nine such Interregnums: Nov 5th to 7th 1873, Oct 8th to 17th 1878, June 6th to 16th 1891, Nov 24th to Dec 5th 1892, Dec 12th to 21st 1894, April 27th to May 1st 1896, July 8th to 11th 1896, Oct 6th to 10th 1911, and June 28th to 29th 1926. I think there was also a ‘Viceregal Interregnum’ when one of our Governors General died in office. There of course is never an Interregnum in the Crown.

LikeLike